In

ter

nat

ion

al J

ou

rn

al o

f

A

sia

n-P

aci

fic H

erit

ag

e S

tud

ies

Government Publication Registration Number

11-1550215-000040-10

Sustainable

Conservation of

Cultural

Heritage

International Journal

of Asian-Pacif i c

Heritage Studies

Su

sta

in

ab

le C

on

ser

vat

ion o

f C

ult

ura

l H

erit

ag

e

Sustainable

Conservation of

Cultural

Heritage

International Journal

of Asian-Pacific

Heritage Studies

Contents

Material Science Analysis of Lacquer for Traditional Repair of Stones

006

in Cambodia

Jiyoung Kim, Seonhye Jeong, Jia Yu, Yongjae Chung

Development of Photogrammetry Education Program

034

for 3D Digital Scan of Cultural Heritage

Jong-wook Lee, Bo-ram Kim, Seon-mi Kim

01

Survey Research Papers on Materials and Techniques

in the UNESCO Chair Programme

Survey Research Papers on UNESCO Chair Research Grant

The 'Sense of Place' Creation through Cultural and Architectural

070

Preservation of Timber Construction of Malay Mosque Architecture

Case Study: Chepor Raja Mosque, Lenggong, Perak, Malaysia

Azizi Bahauddin, Mohd Jaki Mamat

Investigating the Significance of Toponym to the Outstanding

086

Local Values of Heritage Places for the City’s Cultural and

Economic Competitiveness

Eko Nursanty

Preservation and Historical Study of Early Architectural Drawings

100

and Pictorial Records of Heritage Buildings in Seremban, Malaysia

Kum Weng Yong, Doris Hooi Chyee Toe

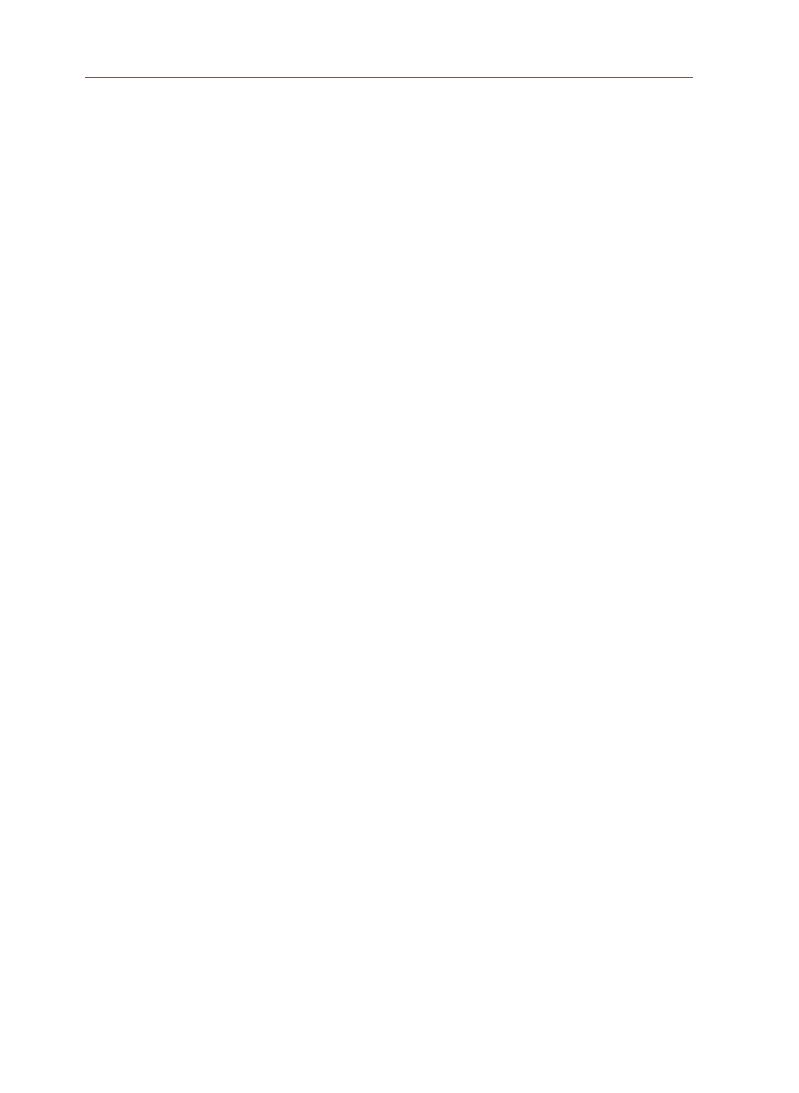

Outstanding Universal Value of George Town, Penang:

124

Surviving Covid-19

Lim Yoke Mui, Khoo Suet Leng

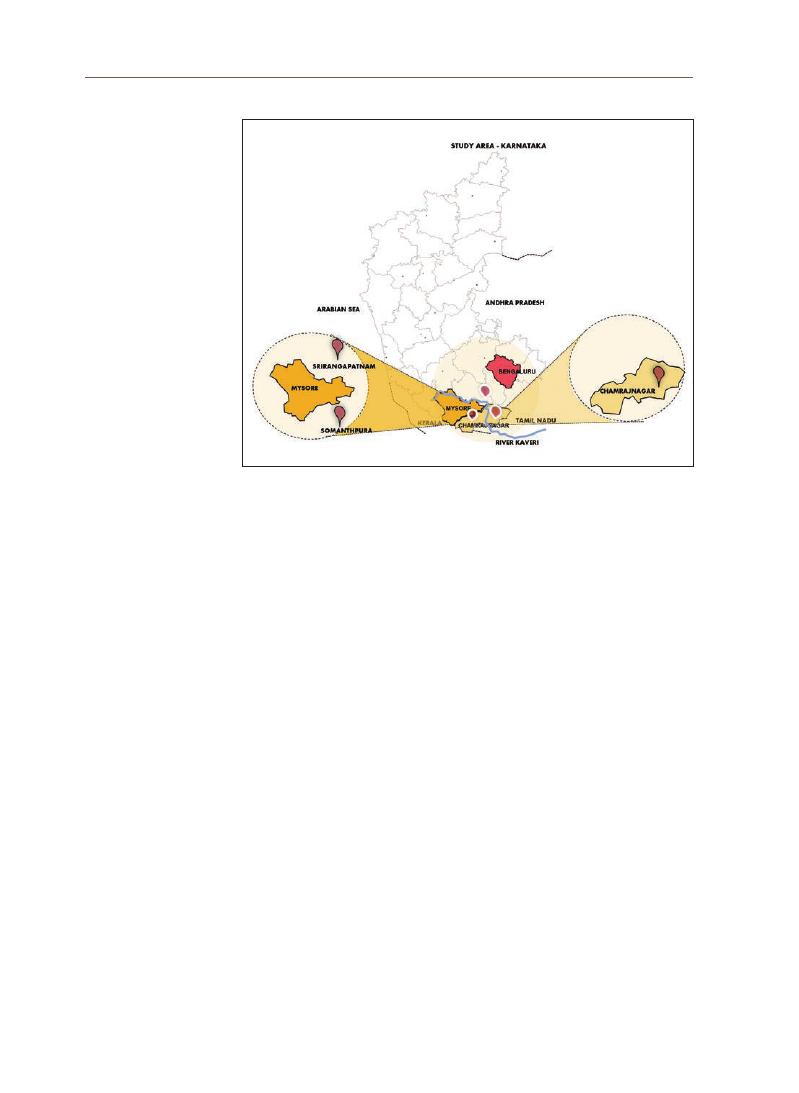

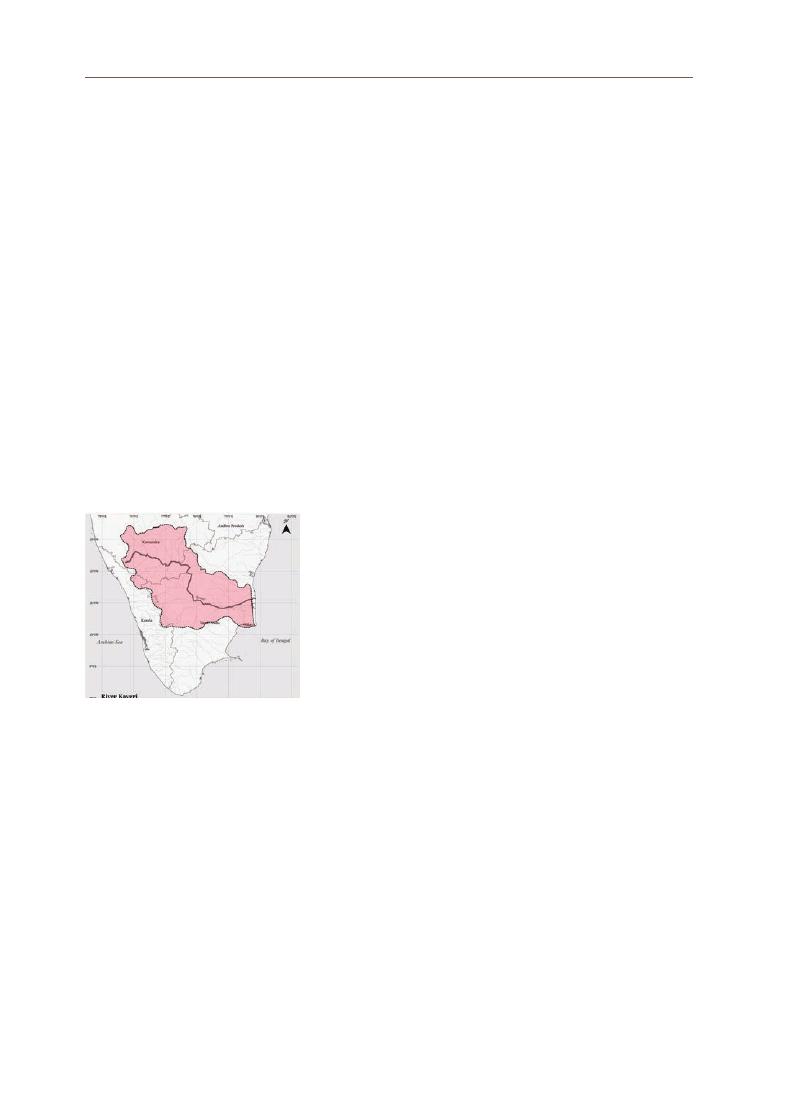

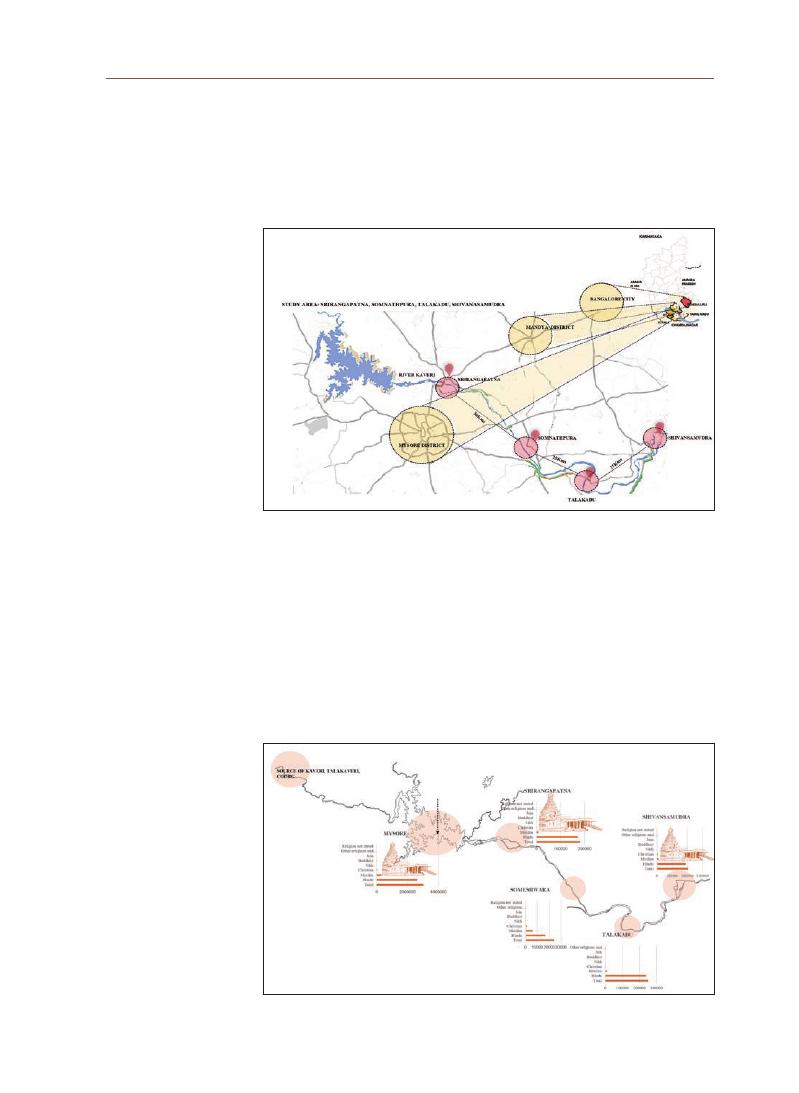

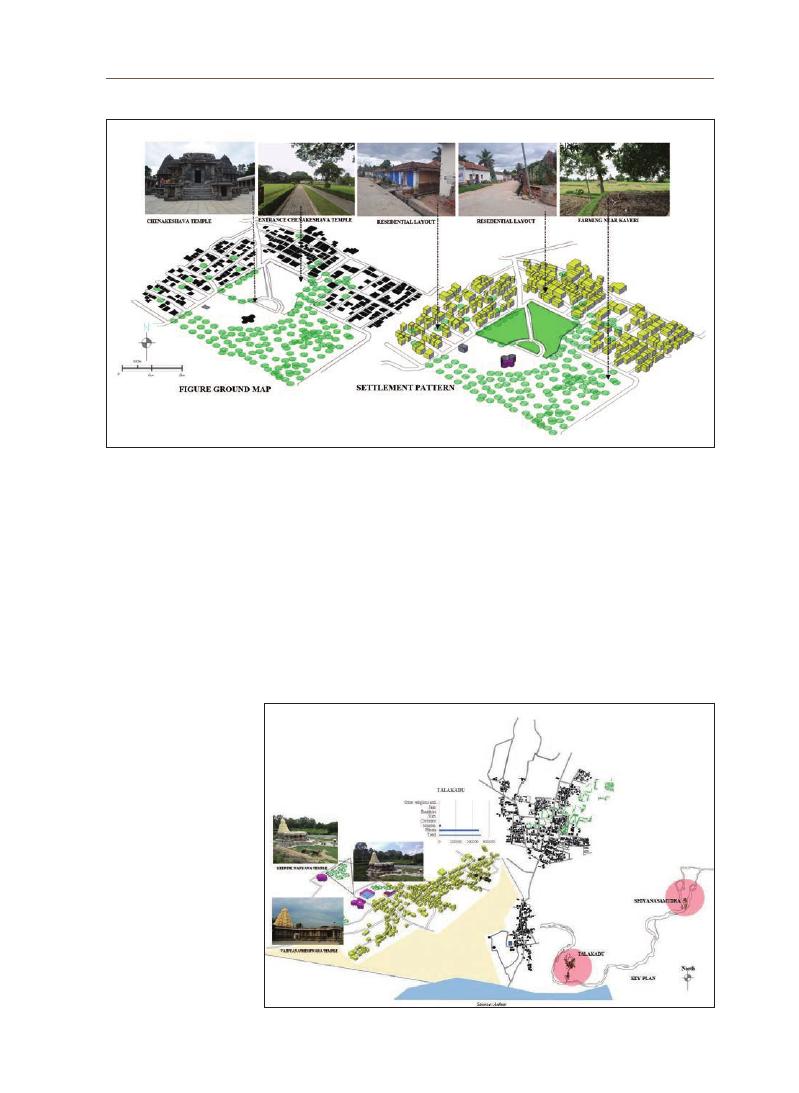

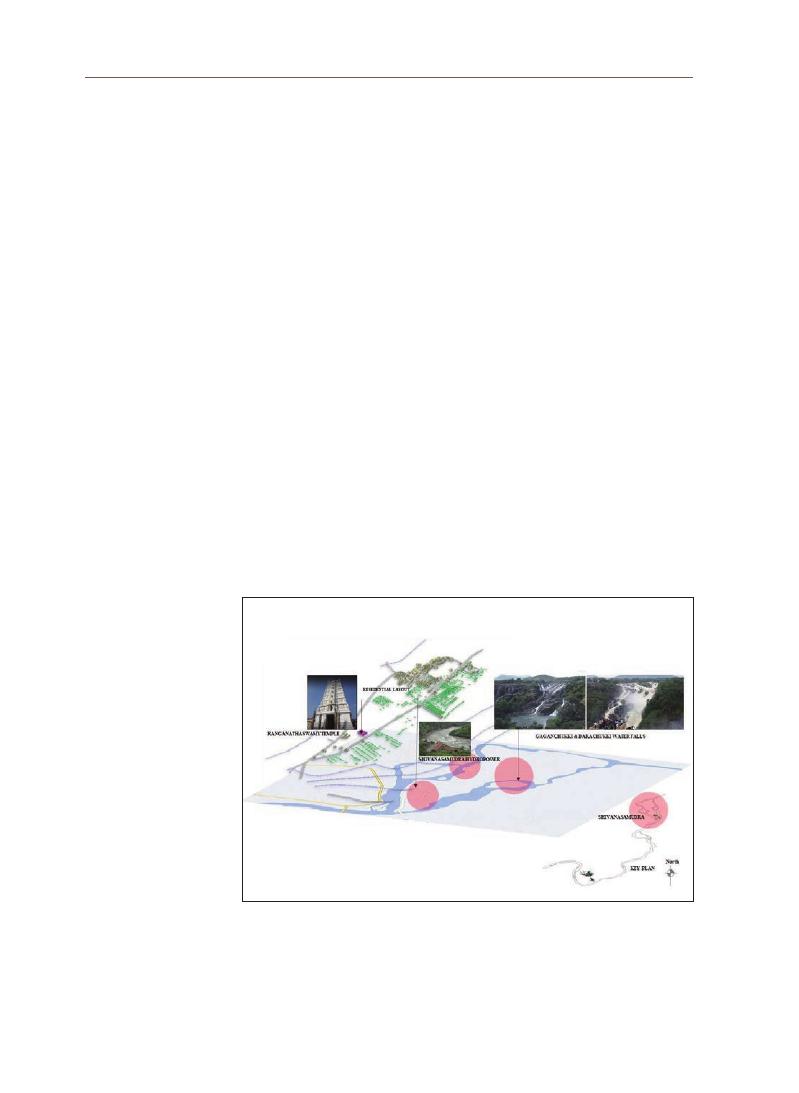

Trace Relationship between Revered River and Sacred Settlements

158

Morphology in South India: Case of Kaveri River

in Context of South Karnataka

Monalisa Bhardwaj, Sudha Kumari G

Traditional Use of Lacquer in Cambodia

180

Vanna LY

02

01

Survey Research Papers on

Materials and Techniques

in the UNESCO Chair Programme

Material Science Analysis of Lacquer for Traditional Repair of Stones in Cambodia

Jiyoung Kim, Seonhye Jeong, Jia Yu, Yongjae Chung

Development of Photogrammetry Education Program

for 3D Digital Scan of Cultural Heritage

Jong-wook Lee, Bo-ram Kim, Seon-mi Kim

Jiyoung Kim Research Professor, KNUCH Industrial Educational Association

Seonhye Jeong Researcher, KNUCH Industrial Educational Association

Jia Yu Researcher, National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage

Yongjae Chung Professor, KNUCH

Material Science Analysis of Lacquer for

Traditional Repair of Stones in Cambodia

Cambodia has been producing various crafts and functional materials

using lacquers since ancient times. Compared to its neighboring countries

of Myanmar and Vietnam, Cambodian traditional lacquers have received

less attention despite their extensive use and long history. This study aims to

evaluate the potential of lacquer as an important material for repairing cultural

properties, and examines its various uses in making and repairing stone

statues in Cambodia. To gather basic data, the composition and characteristics

of lacquer utilized during the ancient times were analyzed scientifically. The

study confirmed that Cambodian lacquer mortar was used as adhesives, fillers,

and finishing materials in the repair of stone statues before the development

of modern synthetic resins. Furthermore, the adhesive lacquer was made of

almost pure lacquer without any inorganic additives, and the filling lacquer

mortar was manufactured by adding a large amount of soil and bone fragments

to the lacquer. The results obtained can provide valuable insights to help revive

the traditional techniques that have been forgotten and to develop technologies

that can be used in the repair of modern stone heritage statues in Cambodia.

Abstract

Survey Research Papers on Materials and Techniques in the UNESCO Chair Programme

01

Jiy

oung Kim

7

1. Background and research aims

Heritage stone statues in Cambodia's Angkor ruins (9th to 14th centuries) have

been worshiped and revered by locals as religious and cultural objects since

their creation. They have been repaired and restored several times after being

destroyed either by changes in social and religious ideology or after natural

damage incurred due to prolonged usage and weathering. Hindu and Buddhist

stone statues found in the ruins were extensively destroyed for religious reasons

and were further damaged by the civil war. Lacquer was extensively used to

restore the damaged stone statues, especially for binding the fallen heads or

arms of the stone statues or for filling in the missing parts. Lacquer comes in

various colors, lusters, and surface textures depending on the mixing ratio of

various organic and inorganic substances which can be altered as per the usage

requirements.

The use of lacquer is confirmed after analyzing the artifacts; however, no

record or data exists on its manufacturing process or the time of its application.

Furthermore, little research has been conducted on the Cambodian lacquer

mortar—hence, it is quite difficult to find information on the traditional lacquer

technology. This research aims to obtain the basic information needed to restore

the traditional lacquer technology by scientifically analyzing the lacquer products

used in the repair and restoration of the stone statues from the ruins of Angkor,

Cambodia.

2. Object and method

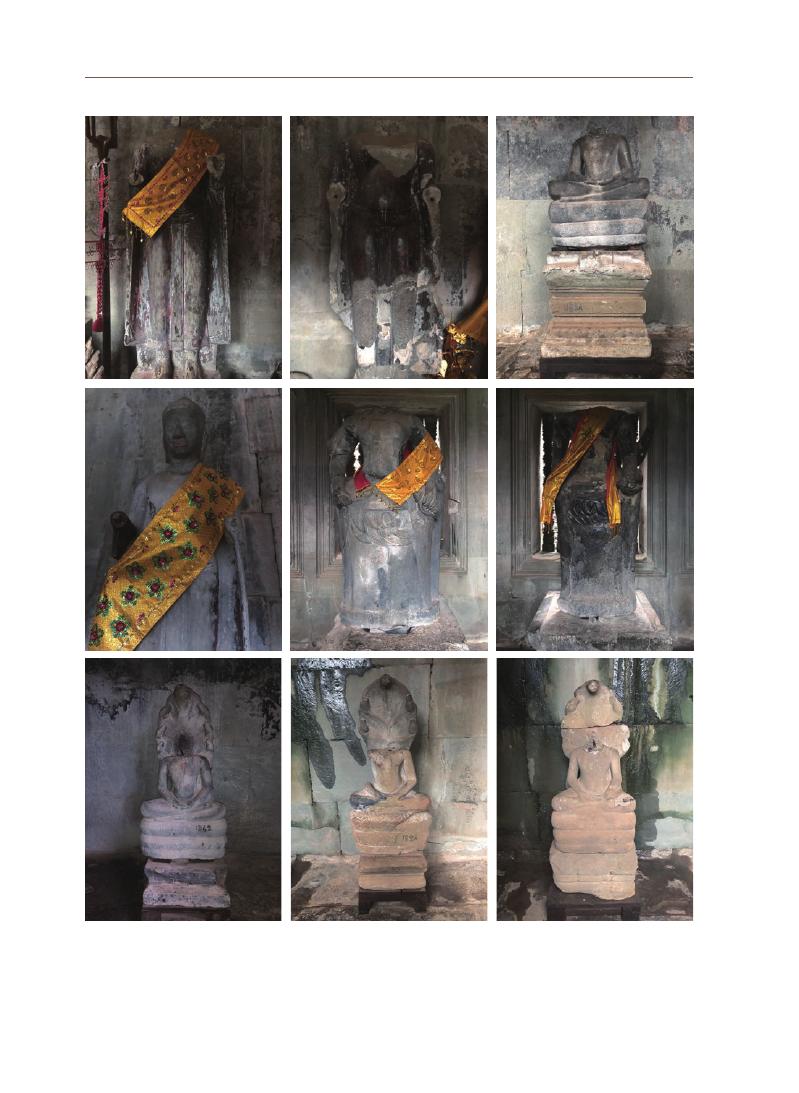

Stone Buddha statues from the Thousand Buddha Gallery at Angkor Wat

and the Pre Rup Temple within the Angkor Archaeological Park were selected

as research subjects. Angkor Wat is located to the south of Angkor Thom and

Pre Rup to the east (Figure 1). Reparation of stone Buddha statues using lacquer

is undertaken at the Thousand Buddha Gallery in Angkor Wat. The Pre Rup

Temple is a Hindu temple dedicated to Shiva. It dates to the 10th century and is

still revered as a sacred place of worship by the residents nearby. There are two

stone statues of Kor and Gor in the central sanctuary, many parts of which have

been restored using the lacquer mortar. The Pre Rup stone statues particularly

showcase various types of lacquer mortar. Preservation treatment performed in

2019 allowed for samples to be collected for further analysis.

The types of lacquer materials identified by naked-eye observation were

classified into adhesives, surface finishing, bonding filling, and molding

restoration. Their macroscopic characteristics were differentiated by type in

Ⅰ

. Introduction

8

detail so that the microstructural characterization and qualitative analytical

methods could be conducted. To determine the additive materials while

manufacturing the lacquer mortar, characteristics such as color, luster, and

hardness were investigated through visual observation, whereas microscopic

observation was performed to identify microstructures and components that

could not be confirmed macroscopically.

Polarized microscopic, stereoscopic microscopic, and scanning electron

microscopic analyses were performed on the lacquer mortar samples collected

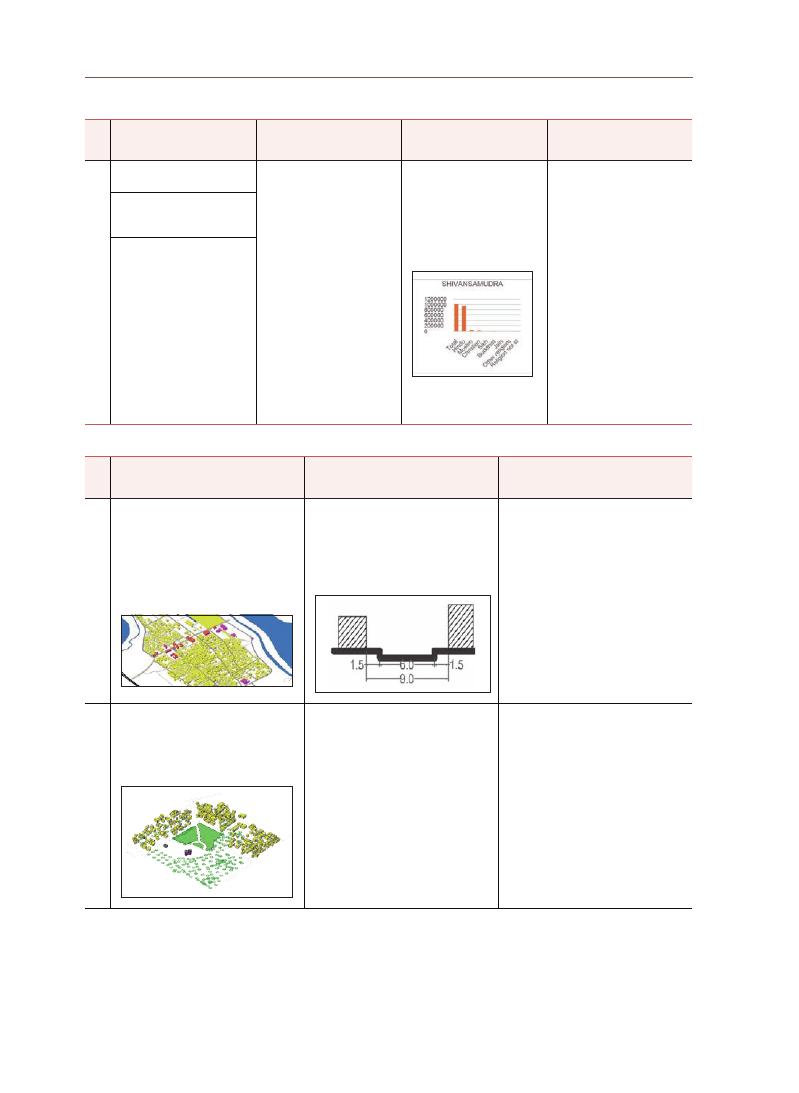

Figure 2. Location of Angkor Wat and Pre Rup temples

Figure 1. Location of Siem Reap, Cambodia

Jiy

oung Kim

9

from two stone statues in the Pre Rup Temple sanctuary which permitted

sample collection. Additionally, X-ray diffraction analysis and SEM-EDS analysis

were conducted to identify its mineral and chemical composition respectively.

Pyro-GC and FT-IR analyses were performed to analyze the organic matter.

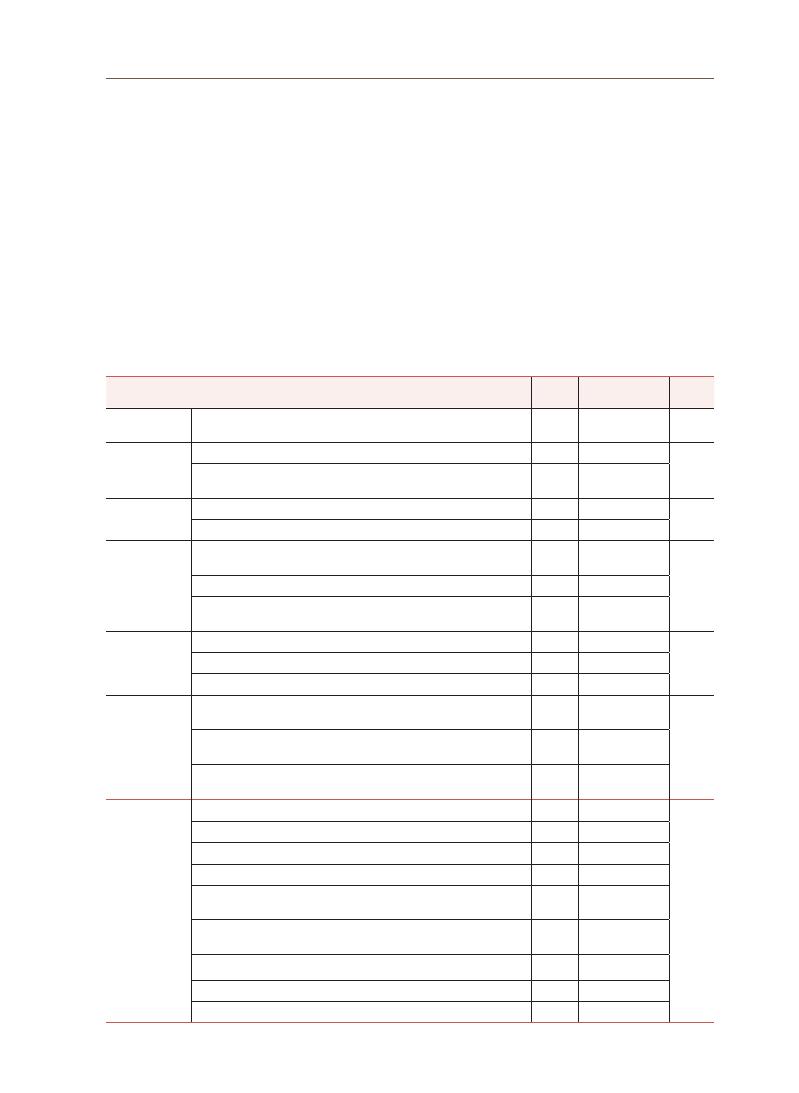

Table 1. Analytical methods

Category

Content

Macroscopy

Color, luster, hardness

Microscopy

Polarizing, stereoscopic, and electronic microscopic analysis

Qualitative analysis

XRD, SEM-EDS, FT-IR, Py-GC/MS

1. Current status

Cambodians have used lacquer to create small objects. Lacquer was

applied to the surface of base materials such as wood, bamboo, earthenware,

ceramics, paper, metal, and leather and was used for finishing, waterproofing,

and decoration purposes. Lacquer has been applied to stone statues from

the pre-Angkor period and became a universal decorative technique during

the Angkor period. Interestingly, lacquer has also been used to repair stone

statues as evident in those found in the Thousand Buddhas Gallery, Angkor Wat.

Lacquer was used to bind broken heads and arms of the stone statues. Iron rods

and bands were also added to reinforce their mechanical strength—a practice

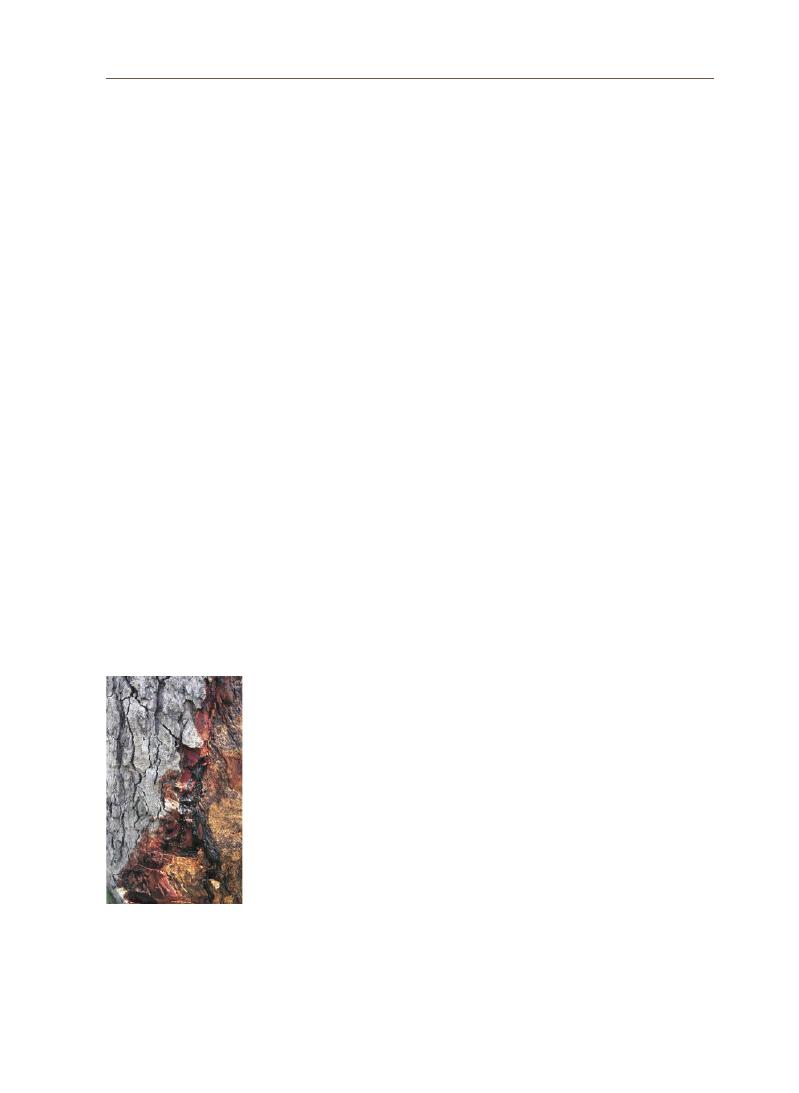

perhaps adopted from the 19th to the early 20th century (Figure 3).

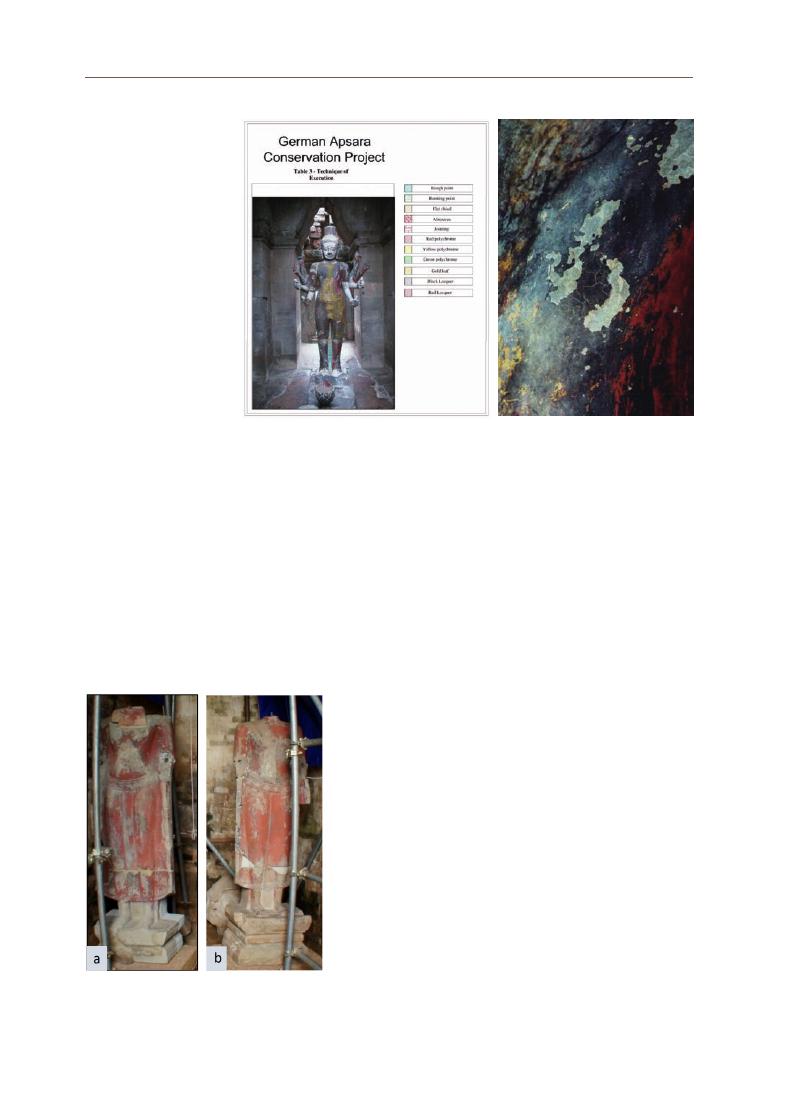

A similar case was observed at the Pre Rup temple. This temple is located

south of East Baray, along with the East Mebon Temple on the north-south axis.

Rajendravarman II (944–968 AD) is assumed to have built it as a Hindu temple

devoted to Shiva either in 1961 or early 1962. The name of the temple means

"

turn the body," hence it is presumed that it might have served as a crematorium,

In the central sanctuary of the temple, there are two Buddhist-style stone

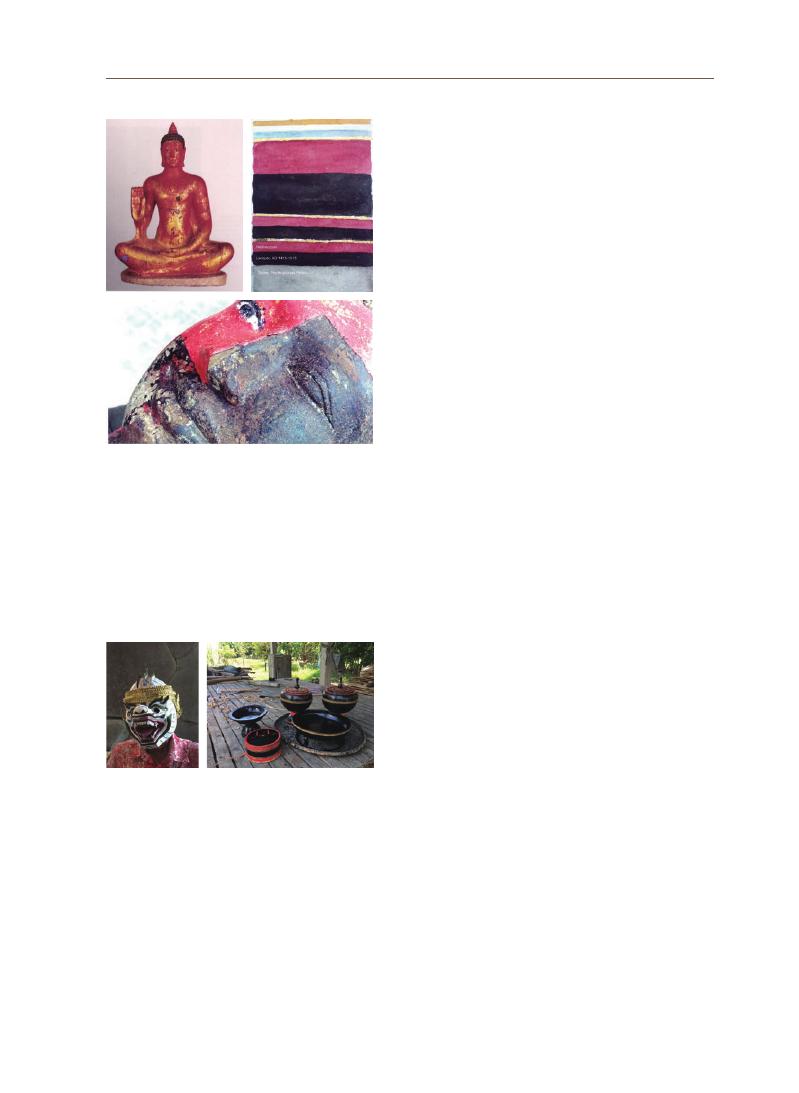

statues called Gor and Kor, which are presumed to have been moved from the

temple of Prasat Bat Chum which is only 1.8 km away from Pre Rup (Figure 4).

These stone statues are considered sacred by the locals and are still handed

down as objects of worship. There are several traces of reparations. The head

has disappeared, and a red pigment covers its surface, and in the case of Kor,

the gorgeous waist decoration remains intact. It appears to have been painted

with a red pigment after lacquer was applied to the entire surface of the stone

statue. It is presumed that lacquer was also used to attach the waist decoration.

Ⅱ

. Current status

and previous

studies

10

Figure 3. Case of lacquered stone statues located in the Angkor Wat 1000 Buddhas Gallery at Angkok Wat

Jiy

oung Kim

11

Figure 4. Stone statues located in the central sanctuary of Pre Rup (left: Gor, right: Kor)

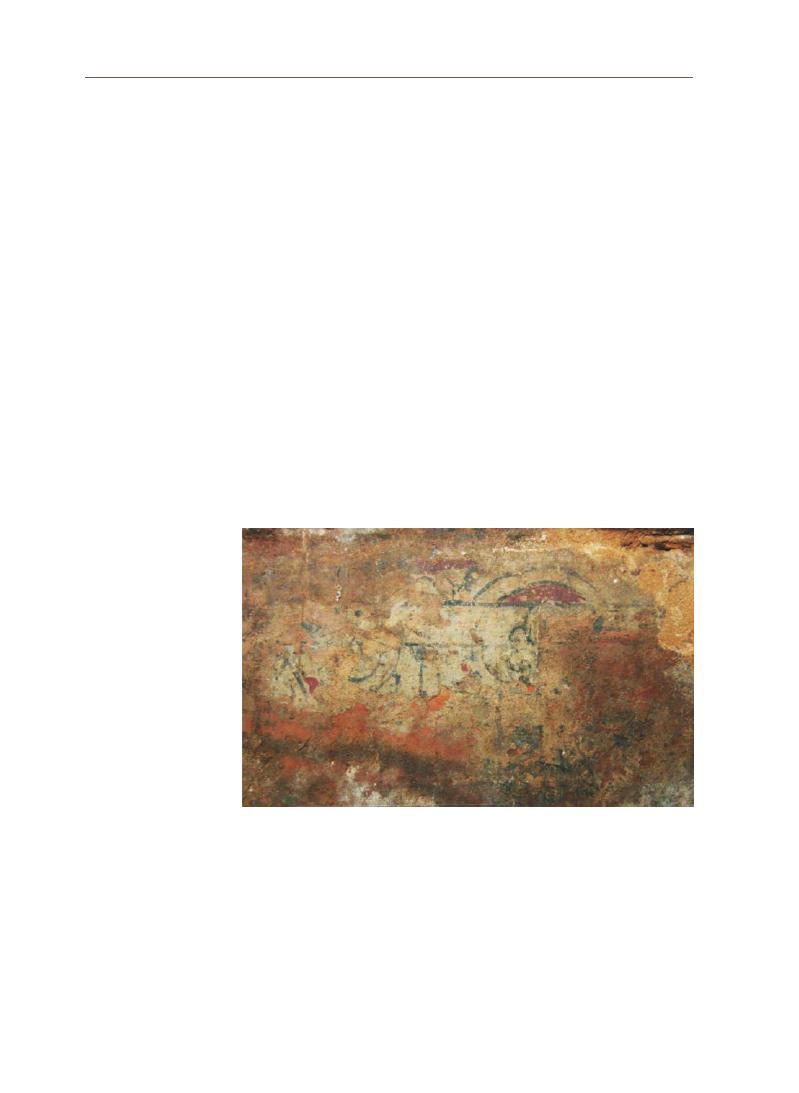

Figure 5. A stone statue located around the library in Phnom Bakheng

Figure 6. Case of stone statues lacquered and painted in the National Museum of

Cambodia. Buddha on Naga/Angkor period-Angkor wat style(left); Head of

Divinity/Angkor period-Bayon style(center); Bas-relief/Post Angkor period(right)

12

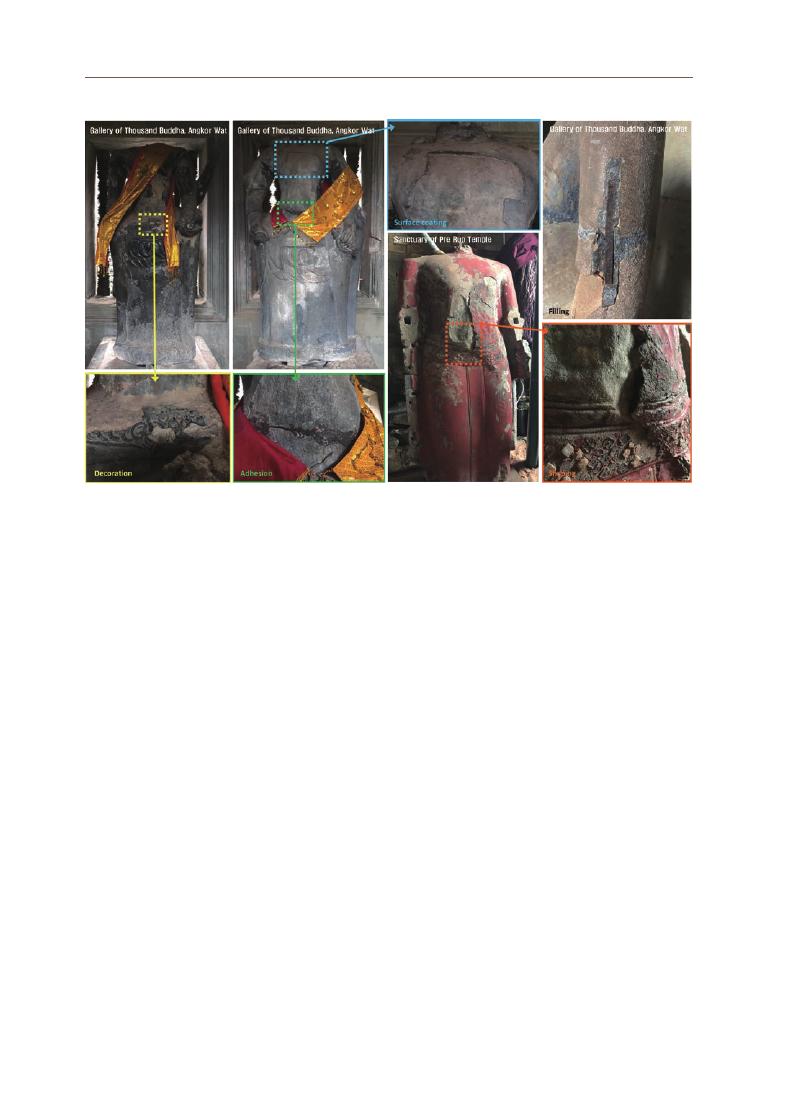

Figure 7. Case of stone statue repair using lacquer

Estimated to have been built during the reign of Yasovarman at the end of

the 9th century, Phnom Bakheng Temple was built two centuries earlier than

Angkor Wat was. Two libraries are located on the east side of Phnom Bakheng,

and stone statues are enshrined inside and around the library located in the

south. Only one stone statue with lacquer, gold leaf, and red pigment remains.

The remaining form suggests that the stone was lacquered, painted with red

pigment, and then covered with gold leaf. The production form is similar to the

stone statues of Pre Rup (Figure 5).

Apart from the stone statues located within the ruins, the National Museum

of Cambodia also possesses a large collection of stone statues with lacquered

remains. Upon searching for sandstone in the inventory of the museum’s

collection system, thirteen stone statues were identified with clear traces of

pigments, gold leaf, and lacquer. The main production periods for these stone

statues are the Angkor period (Angkor Wat style, Bayon style) and the post-Angkor

period (Figure 6).

Lacquer can be used for bonding, filling, and surface finishing while repairing

the stone statues as can be observed in the two stone statues located in the Pre

Rup. Bonding and surface finishing lend a glossy and dense appearance and

looks brown in color. The lacquer used for filling a lost part of the statue appears

gray in color and contains small particles accounting for its high additive content

(

Figure 7).

Jiy

oung Kim

13

2. Previous studies and cases

Research conducted in the last five years was reviewed to confirm the

domestic research trends related to lacquers and the method for scientific

analysis of the material of the statues. Research on lacquers can be classified

into the scientific analysis of the material of the excavated artifacts (focused

on lacquer layer),

research on lacquer craft techniques (mainly lacquerware), and

research on lacquer application for utilizing it as a coating material. The scientific

analysis of the material of the excavated artifacts made of wood lacquer was

conducted as follows: organic materials such as lacquer were analyzed using

FT-IR (Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy) and Py-GC/MS (Pyrolysis/GC/MS);

and inorganic materials such as soil powder were analyzed using EDX (Energy

Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy)

analysis after observation with an optical microscope

and SEM (Scanning Electron Microscope).

Various analytical methods confirmed in previous studies were applied

to Cambodian lacquer samples. The lacquer craft techniques were reviewed

through the literature available on it which was then compared with the craft

techniques for the currently handed down artifacts. A significant portion of the

research on craft techniques was focused on the “mother-of-pearl” technique

handed down to the current artisans. Research reflects that the application of

lacquer to various objects depends on its waterproofing ability, the firmness of

the coating film, and its excellent adhesion ability and that its intended use as a

natural material.

The first Cambodian sculptures were produced in the Kingdom of Funan (2nd

– 6th century)

located in the Mekong Delta. Considered as the cradle of the Khmer

civilization, the first sites with carvings and statues of Indian-style footprints

were discovered here. From the 7th century onwards began the development of

the unique style and craftsmanship of Khmer sculptures. Sculpture continued to

develop in this area and later reached the climax of Angkor sculpture.

At the beginning of the 10th century, Yasovarman I moved the capital of

the Kingdom from Hariharalaya to Angkor. Over a thousand temples and

sanctuaries were built by succeeding kings of the capital between the 9th and

13th centuries owing to the region’s abundant rocks and soil rich. Sculpture-

making peaked in the 12th century, the splendid period of the Khmer Empire.

With the fall of the Khmer Empire, stone carving work became less advanced,

and over time the material was replaced by wood. This was a result of the large-

scale conversions of the locals from Hindu to Theravada in the 15th century.

Since then, lacquer or huge panels have been produced to decorate the wooden

14

sculptures, and the scenes depicting Cambodian culture and history have been

mainly produced there.

Woodwork was centered in Battambang. Cambodian sculptural craft based

on wood or stone almost disappeared during the Khmer Rouge period. During

the period from 1975 to 1979, most of the artisans were persecuted or forced

to farm or earthwork. Since 1992, with the efforts of the European Union and

NGOs, the training and education of young Cambodians have begun to revive the

ancient Cambodian arts and techniques.

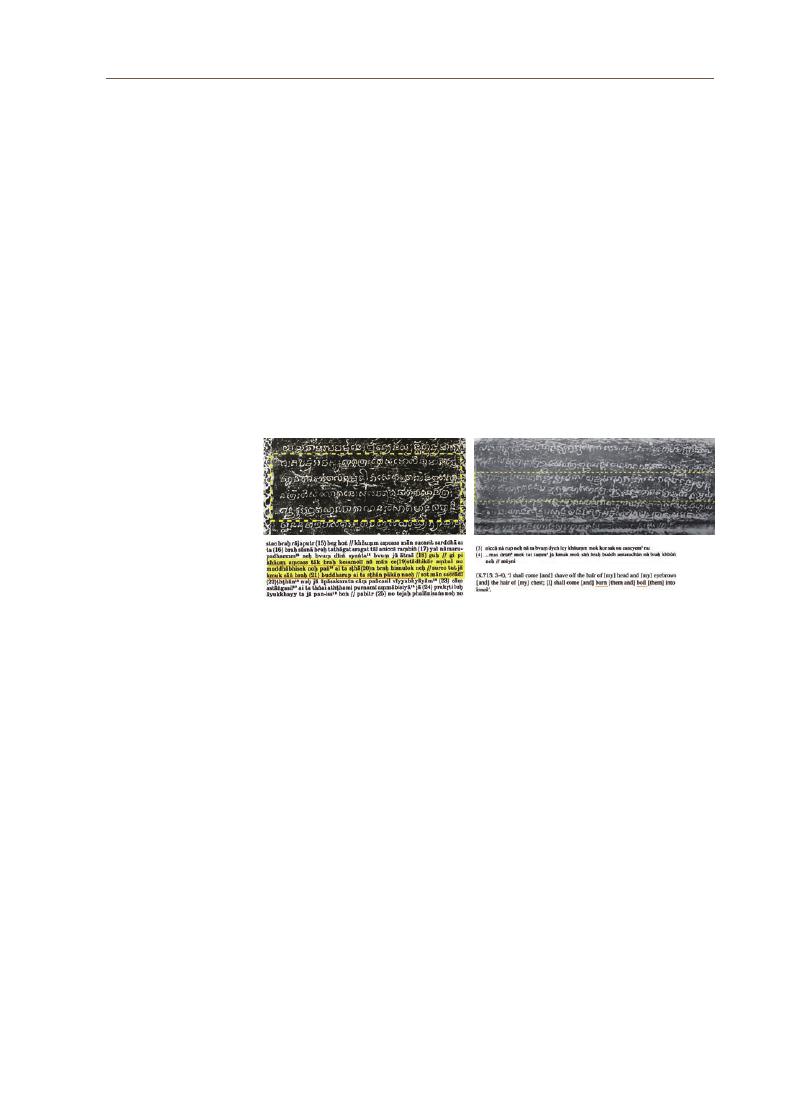

Two stone statues of Pre Rup have been analyzed for conservation from

2018. It was carried out at the SCU (Stone Conservation Unit) which has for long

overseen the preservation and restoration of stone heritage in the Angkor site.

The two stone statues are covered with faint traces of gold leaf and ornaments,

lacquer, and pigments. Prior to conservation, an educational workshop on the

material of the stone statue was held on July 5, 2018. Thirty experts in the field of

stone conservation and archaeology from APSARA (Authority for the Protection of the

Site and Management of the Region of Angkor)

and ACO (Angkor Conservation Office) and GIZ

(

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit)

held a workshop on traditional Cambodian lacquer

and its application.

Participants visited the site of Pre Rup and

discussed the lacquers on the Buddha statue.

Lectures were then delivered on the history of

lacquer, traditional methods of harvesting and

processing, and methods of using materials in

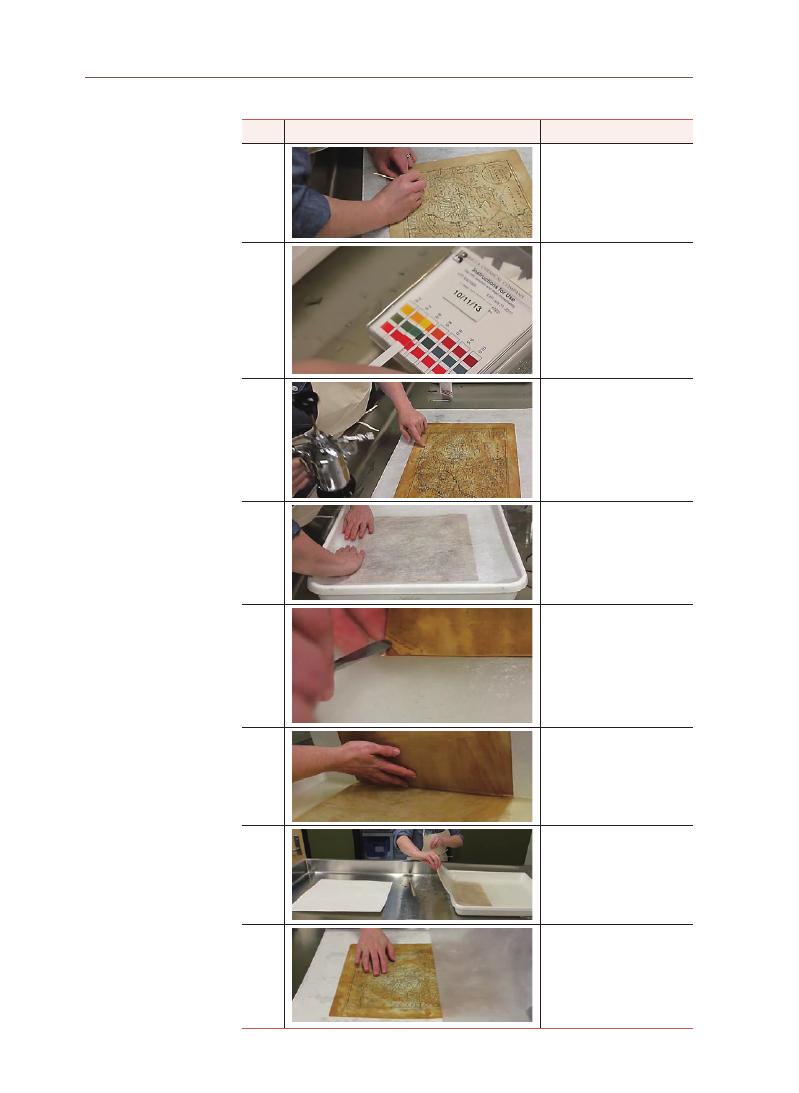

Southeast Asia. Finally, practicals was carried out

and lacquer sampling methods were conducted

based on the theoretical lecture delivered earlier

(

Figure 8).

Under the leadership of GIZ and SCU,

the conservation work of the two Pre Rup stone

statues was completed, and the results were

reported at the 35th Technical Session of the ICC-

Angkor on January 26, 2021. The results reflected

that lacquer was used to fill the cracks in the

statue.

Figure 8. Lecture on Cambodian traditional lacquer

(

source: GIZ)

Jiy

oung Kim

15

Figure 9. Dominant lacquer tree species by region in Asia

1. General characteristics of lacquer

Lacquer is a natural resin/oil-based paint containing catechol compounds,

water, polysaccharides, glycoproteins, and enzymes. The lacquer sap forms a

coating layer (film) via self-polymerization. The lacquer layer is a polymer that is

polymerized by laccase and does not dissolve in various organic solvents. As this

enzymatic reaction is required, it is important to maintain a temperature and

humidity of 25~28 ℃ and 70~80 % when drying the coating layer.

Lacquer is collected from the lacquer tree and used in the form of sap.

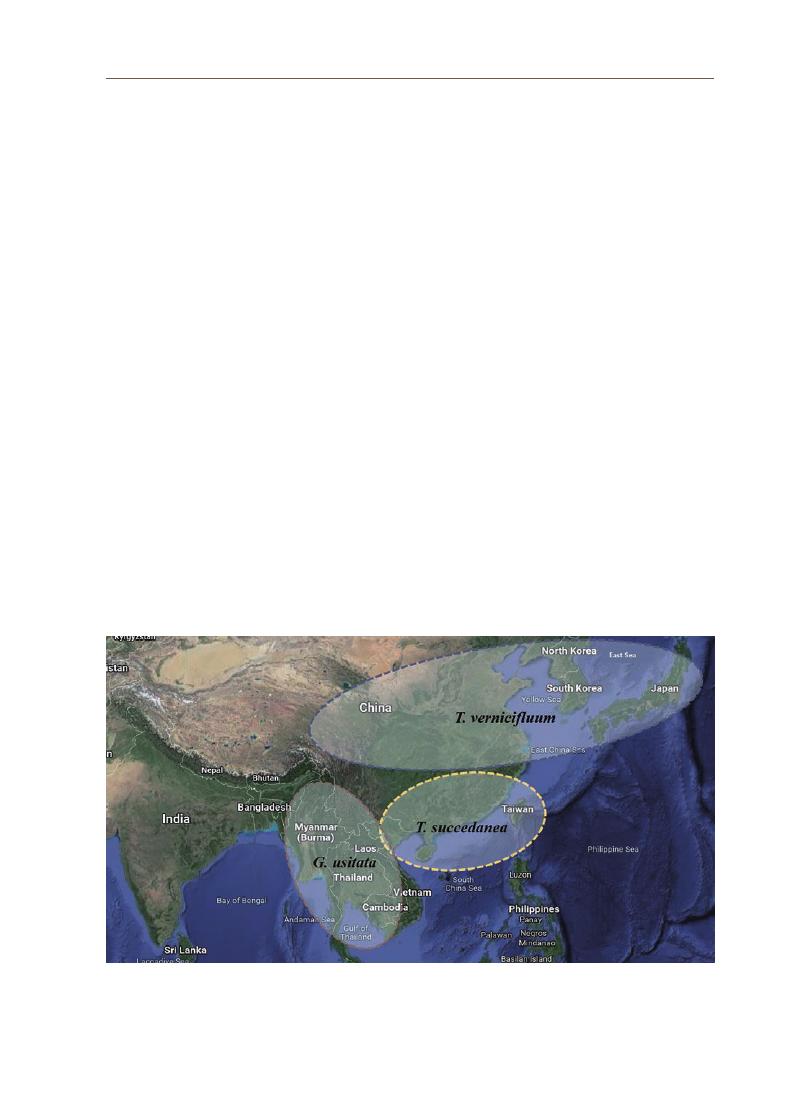

There are three types of lacquer trees.

Toxicodendron vernicifluum grown in

Korea, Japan, and China has a major lipid component of urushiol (C15), and

Toxicodendron succedanea grown in Vietnam and Taiwan has a major lipid

component of laccol (C17).

Gluta usitata, the main lipid component of which is

thitsiol (C17), is grown in Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia. In the case of

the Cambodian lacquer tree, Gluta laccifera is the main lipid component (Figure. 9).

Laccol (T. succedanea) and thitsiol (G. usitata, G. laccifera)-based lacquer sap

contain catechol that, when combined with skin proteins, can trigger an immune

system response (allergic reaction). Lacquer sap is a water-in-oil emulsion. Its

aqueous phase consists of water (20–30%), polysaccharides (5–6%), and laccase

enzyme (~1%), while the oil phase consists of catechol derivatives (60~70%) and

glycoproteins (2–3%).

Ⅲ. Characteristics

of the lacquer

sap and mortar

16

2. Characteristics of functional lacquer

The Cambodian lacquer mortar is a functional lacquer that has been

given plasticity by adding various additives to the lacquer sap. This functional

lacquer has also been traditionally manufactured and used in Northeast Asia,

Korea, China, and Japan. It was called ‘Golhoe’ (bone ash or bone powder). Golhoe

is sometimes called “Tohoe” (clay ash or clay powder), as bone powder was the

main additive in the traditional era. It has been substituted by soil powder in

the modern era. Golhoe was originally used as a filler to prevent deformation

of core shape and to fill gaps in the base material. To make wood lacquerware,

bulky material high in plasticity was needed to fill large gaps in the wooden core

structure. Therefore, various organic and inorganic materials were added to the

lacquer sap. Golhoe was not only widely used to produce wood lacquerware in

Korea, China, and Japan, but also in Nakrang.

Today, golhoe is generally made by mixing soil powder and fresh lacquer sap

in a 1:1 ratio. Other components added to it include bone powder, soil powder,

roof tile powder, animal extracts (animal glue, fish glue, etc.), and vegetable materials

(

tree resin, etc.).

Bone powder, soil powder, and roof tile powder give volume to

the material, especially bone powder and roof tile powder (or pottery powder) as

they are porous which allows lacquer sap to penetrate them. This makes golhoe

dense and more concentrated.

The color of lacquer mortar varies slightly depending on the materials

mixed. It is usually dark brown or dark black. However, when soil powder is

added to it, the red color becomes deeper, and when wood powder or roof tile

powder is added, it takes on a grayish color. Additionally, when the charcoal

powder is mixed, it becomes dark black.1

Lacquer mortar has different workability and properties depending on the

added material. Adding shellfish powder to lacquer decreases its strength,

whereas adding animal bones increases it. For the lacquer mortar to have

excellent adhesive strength, porous material is added to it. In modern lacquer

crafts, it is difficult to supply bone powder or roof tile powder; therefore, coral is

used sometimes.

The adhesion of lacquer mortar is not only determined by the added material

but also by the quality of the lacquer sap itself. The quality of lacquer sap

depends on whether the main components are urushiol, laccol, or thitsiol. Even

for the trees of the same species grown in the same region, the quality varies

greatly depending on the soil and in-situ environment. Therefore, it is necessary

for a person to determine the quality after collecting lacquer sap.

1 Eunjeong Jang, Junghae

Part, Soochul Kim, A Study

on Conservation Materials

of the Lacquer Wares : the

Tohoe and Goksu, Journal of

conservation science, 31(2),

2015.

Jiy

oung Kim

17

Another important factor affecting adhesion is the curing process of lacquer.

While bonding two materials, lacquer is first applied to the surface of one

substrate after which hardening begins. The best adhesive effect can be obtained

by attaching the rest of the pieces at the most appropriate time. This appropriate

time in the curing process is mostly determined by the knowledge and expertise

acquired by the craftsman. Additionally, the supply of water vapor plays an

important role in the curing process of lacquer. If a thick layer of lacquer mortar

is applied, the water vapor does not penetrate sufficiently into the sap; therefore,

the curing process is incomplete, and the adhesive strength is weakened.

As an adhesive, lacquer is usually prepared by mixing starch glue with it.

Lacquer adhesive prepared using barley glue is called Magpul which is used

for bonding pottery.2 The higher the mixing ratio of starch glue, the higher the

viscosity of the lacquer adhesive. There are only a few instances of using lacquer

as an adhesive for stones. Only Goguryeo murals feature a layer of raw lacquer

applied to the stone surface followed by laying on the pigment. In this case, even

when the raw lacquer was directly applied to the stone, a thin and homogeneous

film was produced with good adhesion. The excellent adhesive properties

of such lacquer were also confirmed during the reproduction experiment of

lacquer paintings on granite stones.3

1. Sample selection and macroscopic characteristics

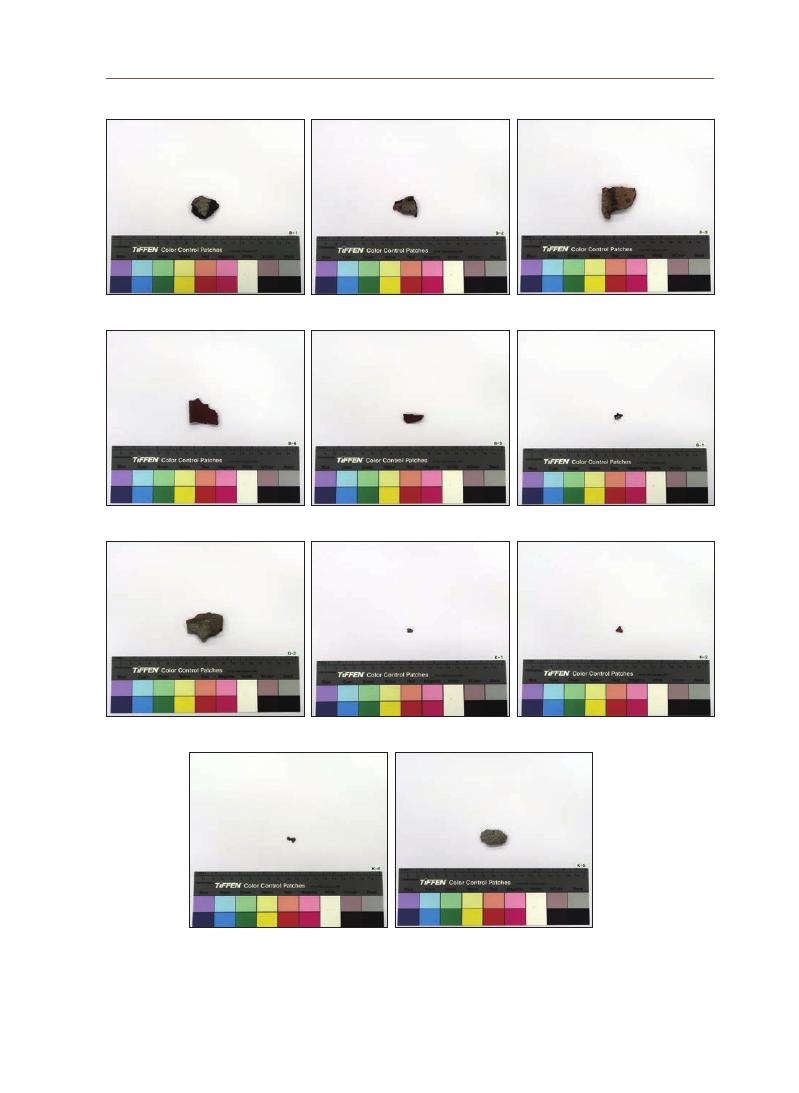

Cambodian lacquer mortar is gray, dark brown, or black. The diversity in

color is determined by the type and composition of the material mixed into it,

such as bone ash in Korea. Black lacquer mortar has a homogeneous color and

texture; therefore, it is presumed that it contains almost no additives or is mixed

with pulverized additives in small quantities. Consequently, gray and dark brown

lacquer mortars have various colored particles added to them in various sizes

(

Figure 10 and Figure 11).

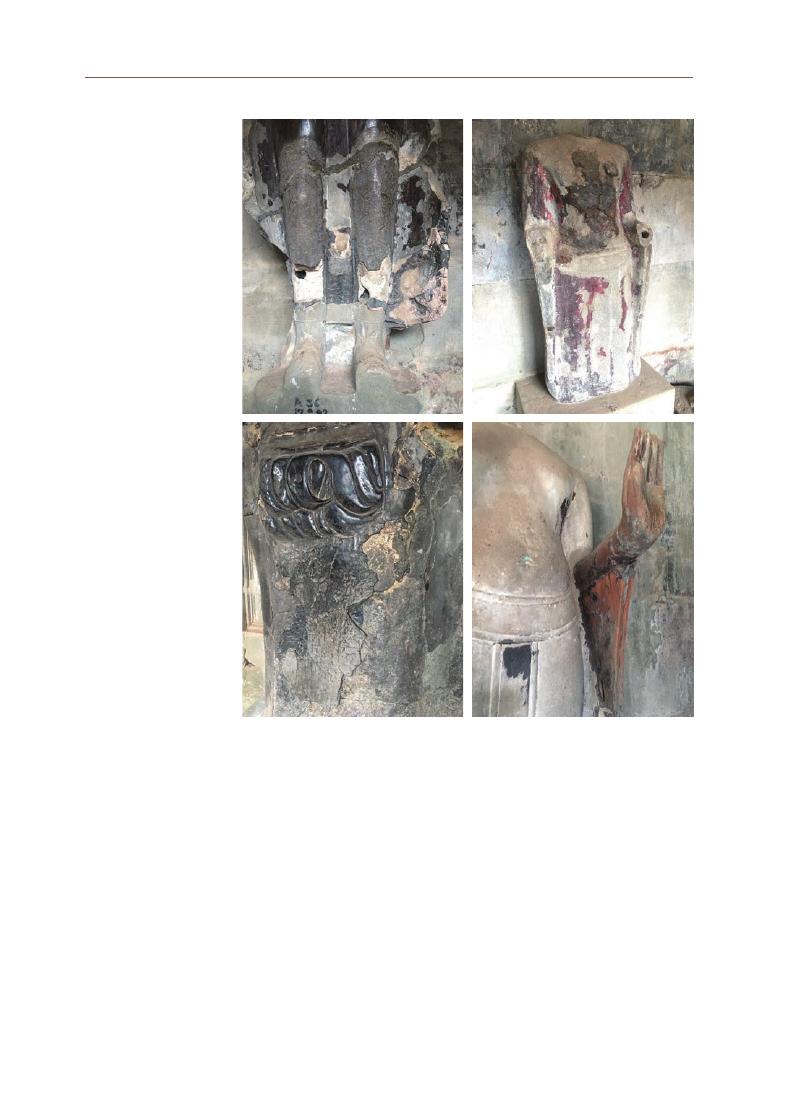

Major parts of the body of the stone statue in the Sanctuary of the Pre

Rup Temple were severely damaged. Though the exact time is unknown, the

lost parts have been restored using a massive amount of lacquer mortar. The

lacquer mortar was dark brown and very hard, lime mortar. Although it was not

observed on the fractured surface of the mortar, the pore surface within the

mortar exhibited a resinous luster. Additionally, traces of lacquer were found to

attach the white ornaments in the decorative belt of the Kor statue.

2 Sungyoon Jang, Lacquer

as Adhesive : Its Historical

Value and Modern

Utilization, Mumhwajae,

49(4), 2016.

3 Jonghun Lee, Haeri Jo,

Lacquer painting for basic

art theory, Hexagonbook,

2018.

Ⅳ

. Analytical

results for

lacquer

mortar

18

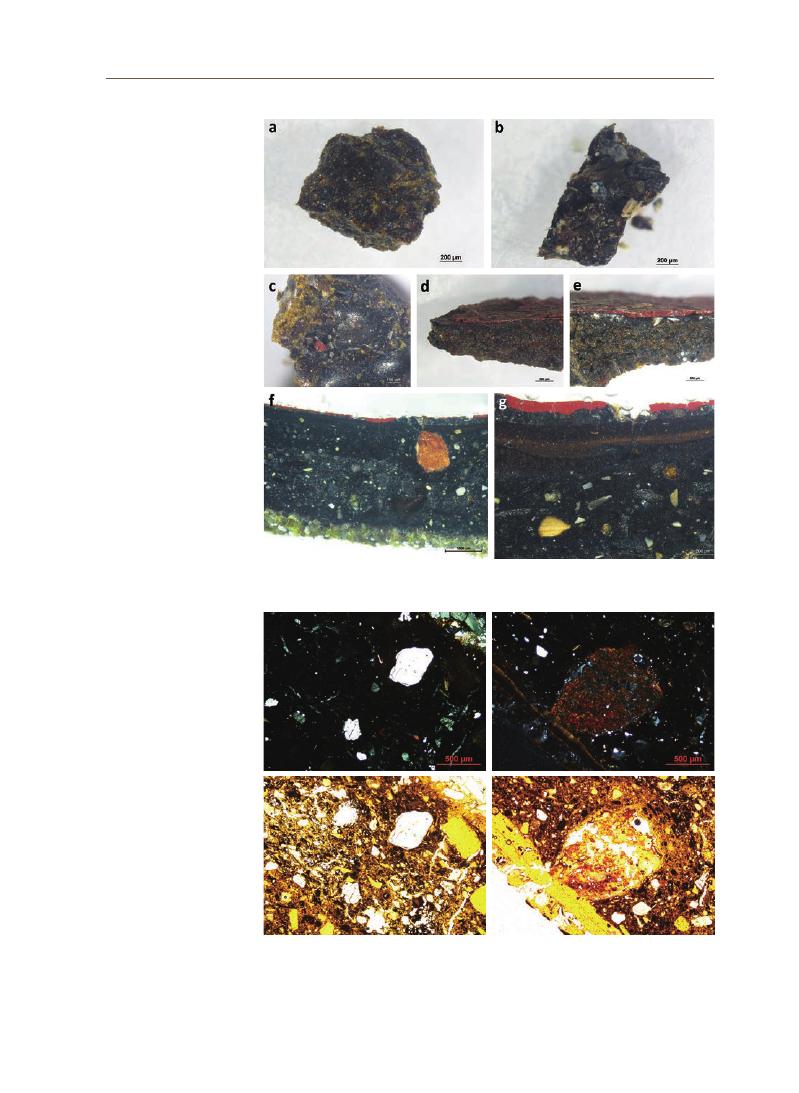

2. Stereoscopic analysis

The microstructural characteristics of the collected lacquer mortar samples

were analyzed. The color of the lacquer was translucent, the thick part of the

specimen was close to blackish brown while the thin part was close to golden or

light yellowish brown (Figures 12a and 12b). The resin luster was also distinct (Figure

12d).

The cross-section of the lacquer mortar attached to the pigment layer

looked blackish brown. The fractured surface was irregular; consequently, the

luster did not appear obvious and the texture looked loose (Figure 12e).

When the cross-section was enlarged, it was observed that there was a thin

layer with a darker color and more pronounced luster than the mortar between

the reddish-brown pigment layer and the lacquer mortar layer (Figure 12f). This

thin layer was considered as a lacquer finish or a lacquer base layer for the

succeeding layer of pigment. The pigment was applied with a uniform thickness

(

Figure 12f).

The cross-section of the specimen was polished and observed under a

stereomicroscope. A reddish-brown pigment layer was clearly observed.

Additionally, it was confirmed that various materials were added to the lacquer

sap. The round particles under the microscope were presumed to be mineral

particulates such as sand and clay, and other irregular angular substances were

Figure 10. Occurence of lacquer mortar in the Sanctuary of Pre Rup Temple

Jiy

oung Kim

19

Figure 11. Lacquer mortar samples collected from the Pre Rup

B‐1

B‐2

B‐3

B‐4

B‐5

G‐1

G‐2

K‐1

K‐2

K‐4

K‐5

20

presumed to be some sort of additives (Figure 12g).

When the polished cross-section was enlarged, it was observed that

several layers had formed between the pigment layer and the mortar layer.

The layer just below the red pigment layer did not contain a large amount of

particulate matter, and the succeeding layer exhibited a layered structure with

diverse thicknesses and colors. Moreover, it was observed that the pores were

distributed throughout the layer of the lacquer mortar. The sizes and shapes of

the pores were not constant (Figure 12h).

3. Polarizing microscopic observation

The thin-section observation of the sample under a polarizing microscope

showed a large number of mineral particles such as quartz and feldspar. The

varied size of the mineral particles corresponded to that of sand, silt, and clay

according to the standard soil classification criteria. A brown aggregate with a

diameter of about 1 mm was found. It was presumed to be an aggregate of clay.

It is likely that silty sand and clay were added to it. Considering that the quartz

and feldspar particles are highly rounded, it was presumed that aqueous clastic

sediments were formed by natural weathering processes rather than being

artificially crushed (Figure 13).

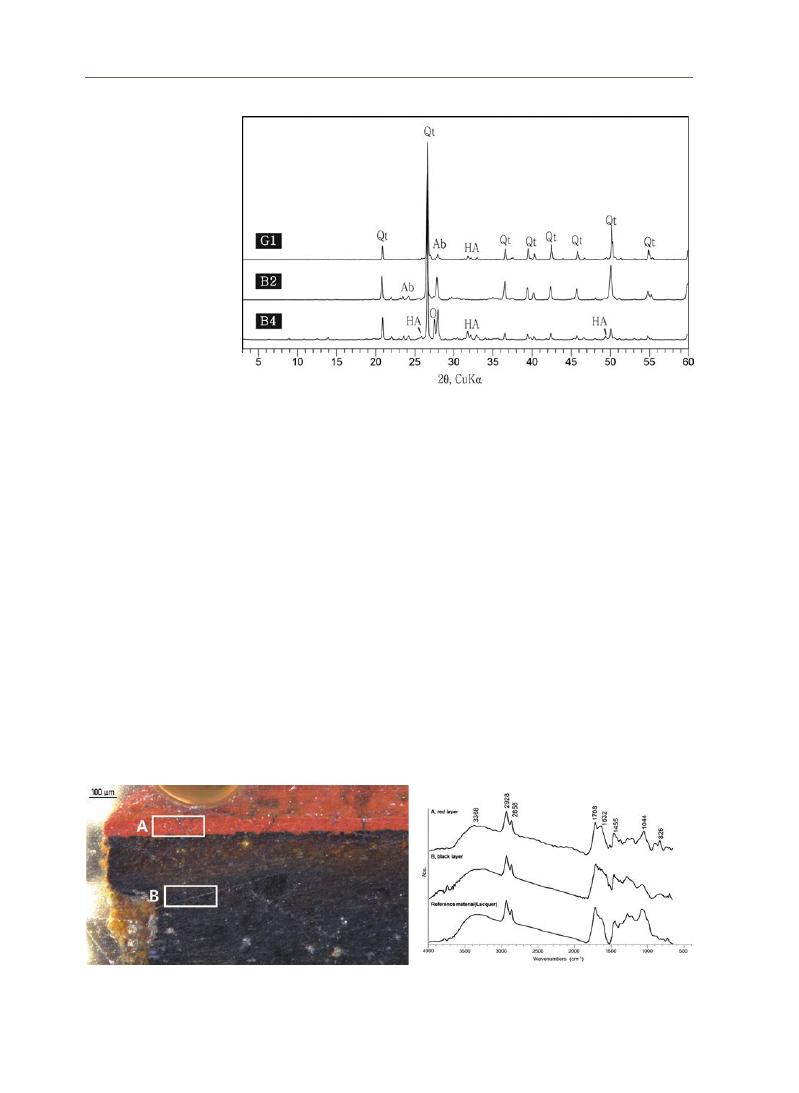

4. X-ray diffraction analysis

We conducted an X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis for three lacquer mortar

samples. Quartz (Qt) and feldspar (Ab, O) were detected the most in the analysis

which meant that a large amount of soil was added to make the mortar. This

was also confirmed by the previous polarized microscopic analysis. Additionally,

hydroxyapatite (HA) was detected. It is an animal bone or tooth component

comprising calcium and phosphorus. It suggested that animal bones or similar

substances were added to manufacture the lacquer mortar (Figure 14).

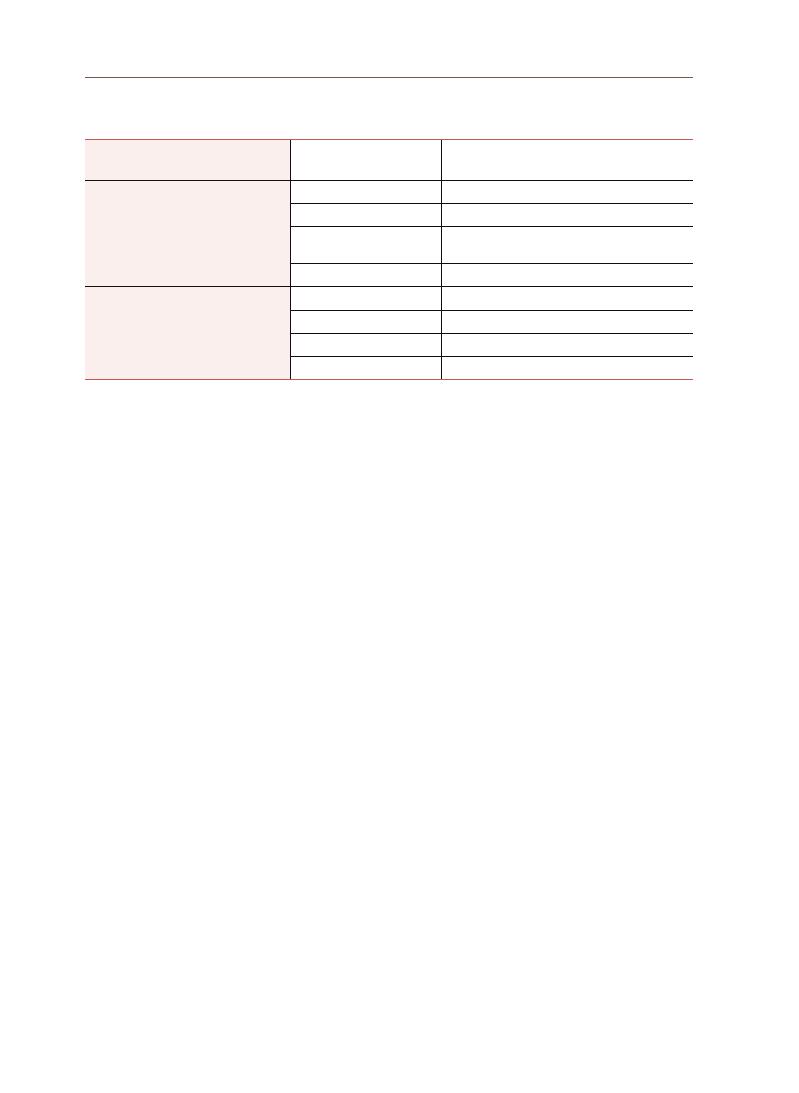

5. FT-IR analysis

Among the samples collected from Pre Rup, those in which lacquer and

pigment were well preserved were prepared as specimens for microscopic

observation. After optical microscopy and SEM observations, the coated part

was polished again and used for FT-IR analysis. An infrared spectrometer (FT-

IR, Hyperion 2000, Vertex 70, Bruker, Germany)

with a microscope and diamond ATR

accessory was used. The following analytical conditions were set: a range of

4000 cm-1 to 650 cm-1 in the measurement area, the number of scans was set at

Jiy

oung Kim

21

Figure 12. Stereoscopic observation of the lacquer mortar samples

Figure 13. Polarizing microscopic images of lacquer mortar

22

64 times, and a resolution of 4cm-1.

An analysis of the red layer (A) and the black layer (B) of the B4 sample

(

Figure. 15)

showed the presence of phenolic hydroxyl groups (-OH) near 3300

cm-1 in a wide range. Methylene groups (-CH3, =CH2), which can be identified

characteristically in lacquer, were analyzed at 2928 cm-1 and 2858 cm-1 (Figure.

16).

Previous studies of thitsiol analysis showed that the main characteristic

absorption peaks were reported at 3500 cm-1 for the hydroxyl group, 2930 cm-1

for the methylene group, 1100 cm-1 for the phenolic hydroxyl group, and 1080

cm-1 for ether.4

After comparing it with the infrared absorption spectrum of the reference

material (lacquer), both the A and B analysis positions of the Pre Rup samples

were confirmed to be lacquer. Significant organic materials other than lacquer

could not be identified.

Figure 14. XRD patterns of the lacquer mortar

Figure 15. Analysis position by layer of lacquer mortar

Figure 16. Infrared absorption spectrum of lacquer

mortar (B4) sample

4 Rong Lu and Tetsuo

Miuakoshi, 2015, Lacquer

Chemistry and Applications,

Elsevier.

Jiy

oung Kim

23

Table 2. Sample status

Name

Collection location

Stereomicrograph (magnification, ×20~60)

G1

K1

K2

K4

6. Py-GC/MS analysis

1) Samples and methods

Among the Pre Rup samples, the specimens were selected according to the

purpose of the lacquer. G1 is a lacquer sample with a clear resin luster taken

from the Gor, and K1 is the adhesive used to decorate the waist of the Kor. K2

is the pigment layer on the left arm of the stone statue of Kor, and K4 is the thin

black and gray film sample (Table 2). Py-GC/MS analysis was performed on G1,

K1, K2, and K4, and the analysis conditions are listed in Table 3.

24

2) Analysis result

(

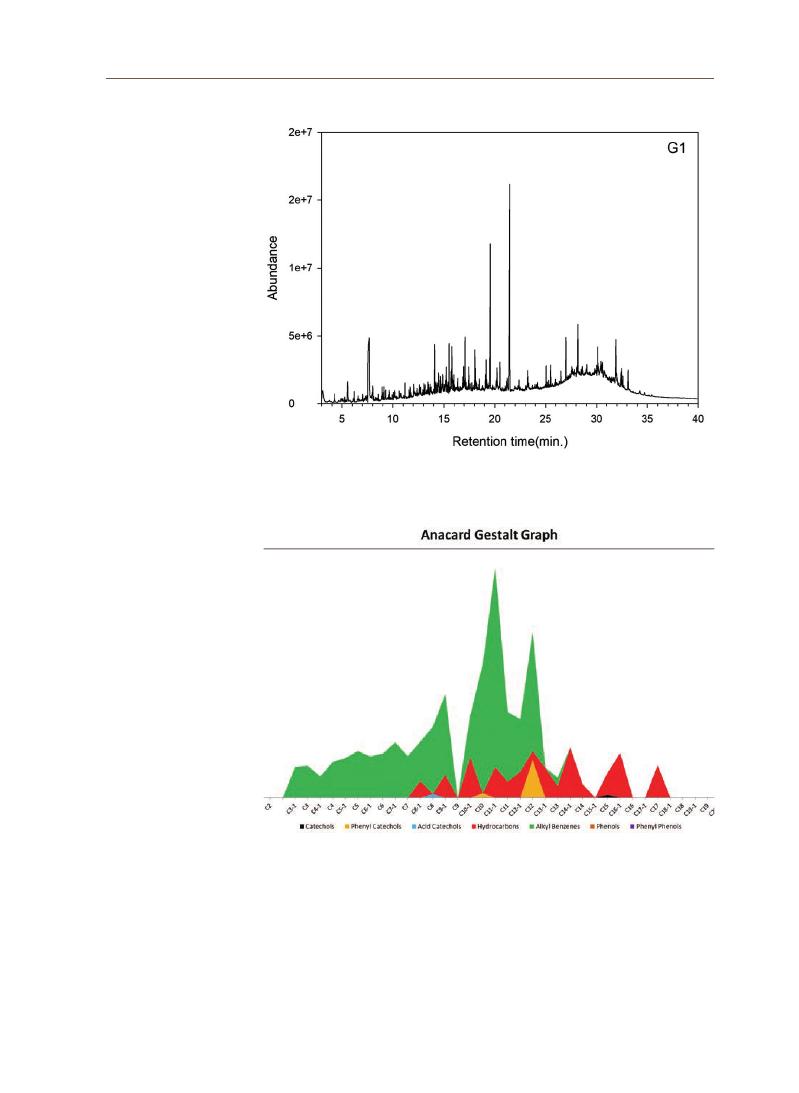

1)

G1

Alkyl benzene and phenyl catechol compounds were detected in thitsiol,

which is the main component of lacquer sap found in lacquer trees in Cambodia.

Ursonic acid methyl ester, nor-alpha-amyrone, and hexakisnor-dammaran-

3,20dione identified in dammar resin were detected as additives. However,

dammar resin has a characteristic that is difficult to identify when it has

deteriorated (requires confirmation with m/z 143). Olean-12en-28-oic acid, 3-oxo-

,

methyl ester was analyzed, and it may be a mastic resin. However, other

characteristic peaks were not identified. Other additives such as oil and protein

were not analyzed. Several fatty acids were identified, but glycerol was not

analyzed; therefore, it is presumed that oil was not used (Figures 17 and 18).

(

2)

K1

A graph of the typical titsi was identified. It was assumed that gum benzoin

was used as an additive (2-propenoic acid, 3-phenyl-, methyl ester/benzoic acid,

4-methoxy-, methyl ester/benzoic acid, methyl ester/methyl p-methoxycinnamate, cis).

A compound (diketodipyrrole) analyzed in glue was identified. Other pyrrole

compounds were not analyzed, and glycine, alanine, and pyridine were detected

(

Figure 19, 20).

Table 3. Instrument and analysis conditions

Pyrolyzer

(

PY-3030D, Frontier Lab, JPN)

Furnace

500℃, 1min

Gas Chromatography

(

7890A, Ahilent, USA)

Inlet

250℃, 20:1

Oven

50℃ (3min.) to 300℃ (5min); 10℃/min

Column

DB-1HT

(

30m×0.25mm id×0.10㎛)

Gas

He 0.5ml/min.

Mass spectrometry

(

5975C, Agilent, USA)

Mass range

m/z 33-600

Transfer temp.

280℃

Ion source temp.

230℃

Quadrupole temp.

150℃

Jiy

oung Kim

25

Figure 17. Pyrogram of G1 sample

Figure 18. Gestalt graph for G1 sample

26

Figure 19. Pyrogram of K1 sample

Figure 20. Gestalt graph for K1 sample

Jiy

oung Kim

27

(

3)

K2

An analysis of the lacquer finish layer under the red layer of the sample

confirmed compounds derived from thitsiol. Additionally, traces of using oil as an

additive (monocarboxylic fatty acids) were found but were not analyzed with certainty

(

Figures 21 and 22).

Figure 21. Pyrogram of K2 sample

Figure 22. Gestalt graph for K2 sample

28

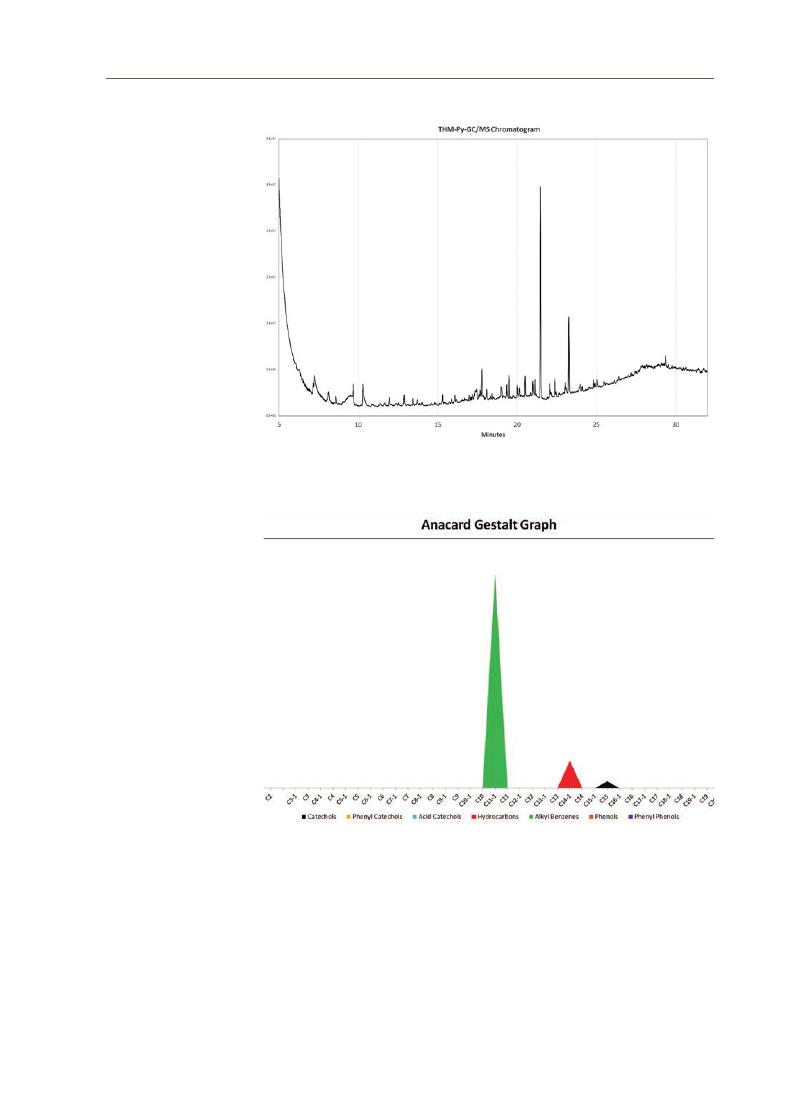

Figure 23. Pyrogram of K4 sample

Figure 24. Gestalt graph for K4 sample

(

4)

K4

Lacquer was identified as typical thitsi, and no other additives such as resin

or oil were detected (Figure 23 and 24).

Jiy

oung Kim

29

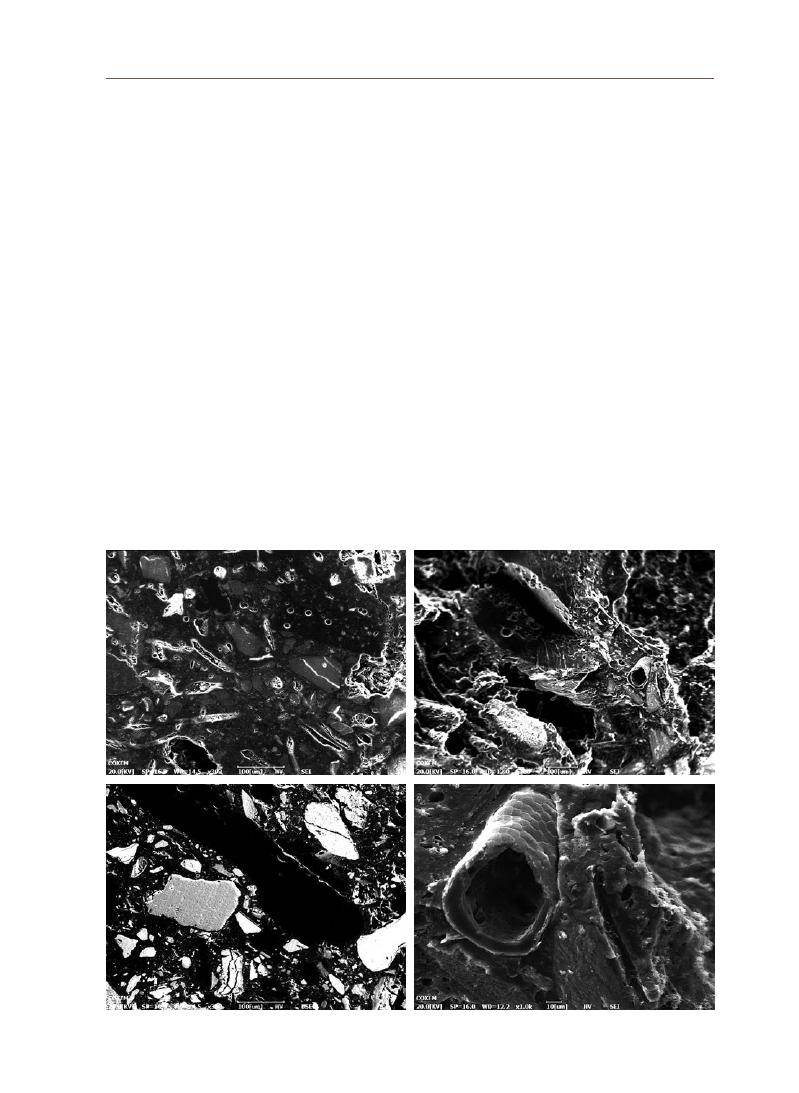

Figure 25. SEM images of the lacquer mortar

7. Scanning electron microscopic analysis

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed. A homogeneous

distribution of small pores was observed at low magnification (Figure 25). The size

of the pores was approximately 10 ㎛. The dense particulates that appeared to

be mineral additives and the smooth texture of solidified lacquer were mixed.

It showed a mixture of sand particles with high roundness and angular to

subangular particulates of smaller sizes. These small angular to subangular

particulates were presumed to be bone powder as they appeared loosely

structured owing to several pores and microcracks. This distinguished them

from sand particles. A tubular and scale-like substance was presumed to be

animal hair.

EDS (Energy dispersive spectroscopy) analysis was performed on the polished

specimens. The dense, smooth, and relatively large particulates were

identified as quartz sand based on the remarkably high Si (silicone) content.

Particulates smaller than quartz were presumed to be clay or feldspar sand

as Al (aluminum) is detected in addition to Si (silicone). An area was found where

30

Ca (calcium) concentration was predominantly high in angular particles. These

particulates were of the bone powder with a high P (phosphorus) content. The thin

pigment layer was identified as a red pigment composed of iron oxide with a

predominantly high Fe (iron) content (Figure 26).

Figure 26. SEM-EDS mapping result

Jiy

oung Kim

31

Ⅴ. Discussion

and

conclusion

A basic scientific investigation was conducted on lacquer mortar used for the

reparation and restoration of stone statues found in Cambodia. Lacquer mortar

is prepared by mixing various additives in lacquer sap. It was used earlier to

bind broken parts of the stone statues and was often used to shape or fill in the

missing parts. Several such cases have been found in the Gallery of Thousand

Buddhas, Angkor Wat, and the stone statues in the Sanctuary of the Pre Rup

Temple.

Various scientific analytical methods were applied to the lacquer mortar

samples collected from the stone statues of the Pre Rup sanctuary. As

confirmed by microscopic observation, XRD analysis, and SEM-EDS analysis,

the lacquer mortar samples contained a large number of additives. Commonly

added materials were sand and bone. Quartz and feldspar sand, and bone

powder with calcium and phosphorus were identified. FT-IR and Py-GC/

MS analyses determined the lacquer as containing thitsiol, which is the main

component of lacquer tree sap grown in Myanmar, Cambodia, and Thailand. In

addition to thitsiol, resin-based substances collected from trees and barks, such

as dammar and mastic, were also identified. Thitsiol and gum benzoin was also

detected in the lacquer adhesive used in the decoration of the Pre Rup statue.

Only lacquer thitsiol was identified in some lacquer specimens without any other

substances.

Cambodian lacquer mortar is very similar in material to Golhoe from Korea,

China, and Japan. According to the research data on Golhoe from Korea, the

additives were soil, charcoal, and bone powder , although the component and

ratio altered slightly with time. It is believed that wood powder,5 wheat flour, coal

powder, and horse incense were also used,6 although obvious analytical data or

literature data to prove it were insufficient. The inorganic materials added to the

lacquer in Cambodia, Korea, China, and Japan are presumed to be almost the

same. Organic additives such as dammar, mastic, and gum benzoin were found

in Cambodian lacquer mortar. It was reported in previous research that rice

husk ash, fatty acids, and tannins were also identified in Cambodian lacquer.7

However, this was not clearly confirmed in this study. Several materials added

to lacquer to make it functional vary greatly depending on region and era.

Accordingly, the components to be detected also vary depending on the type of

object analyzed. Additionally, it is possible that the deterioration of old lacquer

also affected the analysis results.

Only a few studies on Cambodian lacquer exist as scientific analyses on

it are rare in comparison to those on lacquers found in Myanmar or Vietnam.

5 Seulyoung Lim, The Modern

Transformation of Bone

Ashes and Its Cause, Korean

journal of art history, 305,

2020.

6 Eunjeong Jang, Junghae

Part, Soochul Kim, A Study

on Conservation Materials

of the Lacquer Wares: the

Tohoe and Goksu, Journal of

conservation science, 31(2),

2015.

7 Haana Szczepanowska and

Rebecca Ploeger, 2019,

The chemical analysis of

Southeast Asian lacquers

collected from Forests and

workshops in Vietnam,

Cambodia, and Myanmar,

Journal of Cultural Heritage.

32

Therefore, based on the results of this basic research, it is necessary to

conduct additional analysis and in-depth studies in the future to determine the

characteristics of lacquer from different Cambodian regions and periods. The

results obtained from this study will be used as basic data for the same and to

revive the traditional lacquer techniques of Cambodia.

Jiy

oung Kim

33

References

Acknowledgements

Junghae Park, Yonghee YI, A study on investigation of gold painting technique

in the lacquerwares of Goryeo, Conservation science in museum, 14,

2013.

Jonghun Lee, Haeri Jo, Lacquer painting for basic art theory, Hexagonbook,

2018.

Kwonwoong Lim, Jonghun Lee, A study on Sobyuks : technique of Goguryeo

Tomb Murals, The KoguryoBalhae Yonku, 30, 2008.

Seulyoung Lim, The Modern Transformation of Bone Ashes and Its Cause,

Korean journal of art history, 305, 2020.

Sungyoon Jang, Lacquer as Adhesive : Its Historical Value and Modern

Utilization, Mumhwajae, 49(4), 2016.

Eunjeong Jang, Junghae Part, Soochul Kim, A Study on Conservation Materials

of the Lacquer Wares : the Tohoe and Goksu, Journal of conservation

science, 31(2), 2015.

Haana Szczepanowska and Rebecca Ploeger, 2019, The chemical analysis of

Southeast Asian lacquers collected from Forests and workshops in

Vietnam, Cambodia, and Myanmar, Journal of Cultural Heritage.

Masako Miyazato, Rong Lu, Takayuki Honda, Tetsuo Miyakoshi, “Lao lacquer

culture and history—Analysis of Lao lacquer wares”, Journal of Analytical

and Applied Pyrolysis, 103, 2013.

Rong Lu and Tetsuo Miuakoshi, 2015, Lacquer Chemistry and Applications,

Elsevier.

Yingchun Fu, Zifan Chen, Songluan Zhou, Shuya Wei, “Comparative study of

the materials and lacquering techniques of the lacquer objects from

Warring States Period China”, Journal of Archaeological Science, 114,

2020.

This research was funded by the 2021 UNESCO Chair Research Grant Project of

Korea National University of Cultural Heritage.

Jong-wook Lee Professor, KNUCH

Bo-ram Kim Researcher, KNUCH

Seon-mi Kim Researcher, KNUCH

Development of Photogrammetry

Education Program for 3D Digital Scan of

Cultural Heritage

Various interdisciplinary studies are needed in the field of heritage, and the

fourth Industrial Revolution has established projects utilizing digital technology

related to the excavation, conservation, and utilization of heritage. However,

owing to the characteristics of digital technology, it is not easy for laypeople

to access cultural heritage through it, which is an aspect field of heritage that

requires to be worked upon in the future.

This study thus developed a photogrammetry education program—a digital

technology for workers engaged in the field of heritage. The concepts and

definition of digital heritage were first examined. Digital heritage is a digital

approach to heritage that involves the transformation of physical heritage into

a digital form. Additionally, the concept of born-digital heritage is also defined

as digital heritage in accordance with the Charter on the Preservation of Digital

Heritage.

The importance of digital education in the field of heritage is recognized by

several countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and South

Korea. The necessity for the education and application of digital technology is

emerging with the complex changes in the functioning of museums. Hence,

we intend to encourage the use of digital technology in the field of heritage by

developing educational programs for people working in this field in the Asia-

Pacific region.

In conclusion, photogrammetry, aiding in acquiring and generating 3D data,

was selected, and its basic principles, preparations, and practical methods

were studied. Consequently, the goal is to acquire photogrammetry skills easily

through an educational handbook, irrespective of the location of the workers, by

creating an educational program that can educate workers engaged in the field

of heritage in the Asia-Pacific region.

Abstract

Survey Research Papers on Materials and Techniques in the UNESCO Chair Programme

02

35

Jong

-w

ook Lee

1. Cultural Heritage

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)

defines heritage as the living heritage inherited from our ancestors to be passed

on to future generations (UNESCO, n.d.). Currently, South Korea uses the term

cultural property (문화재; Munwahjae) as a legal term for cultural heritage. The

Cultural Heritage Protection Act, enacted to promote the cultural improvement

of the people and to contribute to the development of human culture, defines

cultural heritage as follows.

The term “cultural heritage” in this Act means artificially or naturally formed

national, racial, or world heritage of outstanding historic, artistic, academic, or

scenic value.

(Cultural Heritage Protection Act, Article 2 (definition), 2020)

As defined above, cultural heritage lives with us in the present, and it is

important to pass on its value intact to the next generation (Venice Charter 1964).

This means that cultural heritage must be properly excavated, conserved,

managed, and utilized in the communities in which it exists. John Ruskin (1849,

179)

argued that cultural heritage should be utilized by all generations and that

the present generation has no right to alter or destroy it.

However, it is important to utilize cultural heritage sustainably, because the

conservation of cultural heritage is to respect not only the present generations

but also the future generations. Various methods have been suggested to utilize

cultural heritage sustainably and to maintain its integrity. This study recognizes

the digital formats of the resources and information related to cultural heritage

as the concept of digital heritage. We will suggest ways to maintain the

authenticity and integrity of cultural heritage.

2. Digital Heritage

Since the 1990s, with the advent of the Information Age, the digitization of

information on heritage has been undertaken. It has brought about changes

in the museum and cultural heritage management systems (Ahn and Kim 2016,

5).

In accordance with these changes, UNESCO and several other international

organizations have begun to pay attention to the concept of digital heritage. In

2001, the UNESCO Council discussed the preservation of digital heritage, paying

special attention to the issues of digital preservation faced by the European

Commission on Preservation and Access (ECPA) (Ahn and Kim 2016, 5).

Ⅰ. Digital

Heritage

36

Accordingly, UNESCO drafted the Charter on the Preservation of Digital

Heritage in 2003, which outlined the definition of digital heritage, approach

towards it, threats from loss of cultural heritage, the need for action, and digital

continuity. The Charter defines digital heritage and its scope as follows.

The digital heritage consists of unique resources of human knowledge and

expression. It embraces cultural, educational, scientific and administrative

resources, as well as technical, legal, medical and other kinds of information

created digitally, or converted into digital form from existing analogue resources.

(UNESCO, 2003)

As mentioned above, digital heritage not only includes the cultural heritage

expressed and reproduced in digital form but also the concept of born-digital

originally created by digital technology. In particular, Mckenzie and Poole

extended the concept of digital heritage to a ‘digital approach to heritage’ (Mckenzie

and Poole 2010 cited in Ahn and Kim 2016, 6–7).

Several relevant international charters

can confirm the importance and scope of digital heritage.

3. Charters on Digital Heritage

International charters on digital heritage include the Universal Declaration

on Cultural Diversity (2001), Charter on the Preservation of Digital Heritage

(

2003),

UNESCO Recommendation concerning the Promotion and Use of

Multilingualism and Universal Access to Cyberspace (2003), The London Charter

for the Use of 3-Dimensional Visualisation in the Research and Communication

of Cultural Heritage (2006), and Recommendation Concerning the Preservation

of, and Access to, Documentary Heritage Including in Digital form (2015). These

charters deal with the relationship between culture and the digital world and

display the following characteristics.

1. Professionals in the Field of Heritage

Various types of workers are employed in the heritage field based on their

qualifications. There are museum and art gallery curators, culture and arts

educators, cultural tourism docents, cultural heritage repair technicians (Kim

2012),

amog others. For this study, a museum curator, who practices cultural

heritage, was selected to take an educational program on digital heritage. The

International Council of Museums (ICOM) Korean Committee defines museum

workers as follows.

Ⅱ. Education

on Digital

Heritage

37

Jong

-w

ook Lee

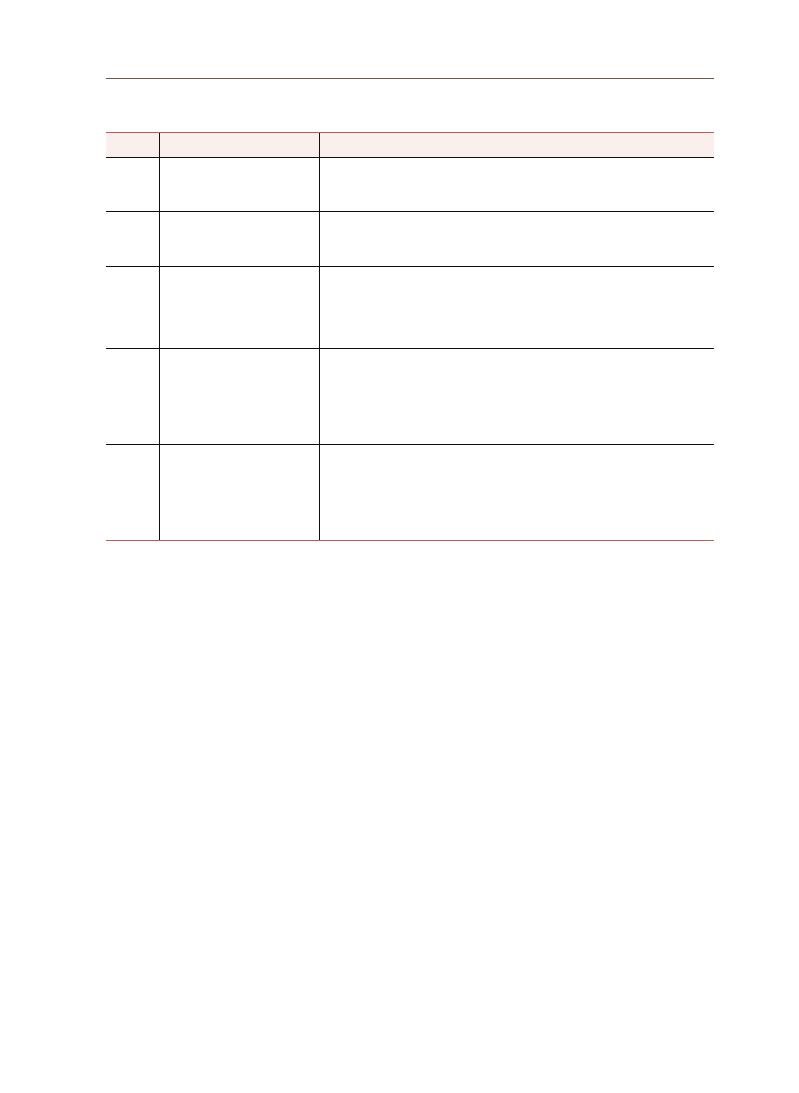

Table 1. Charters on Digital Heritage

Year

Charters

Contents

2001

Universal Declaration on

Cultural Diversity

Article 6 declares cultural diversity for all and codifies measures to ensure

the free flow of ideas in text and images, while at the same time allowing

all cultures to express and promote themselves.

2003

Charter on the Preservation

of Digital Heritage

Establishment of a concept for the conservation and management of

UNESCO digital heritage, guaranteeing access to digital heritage including

born-digital heritage.

2003

UNESCO Recommendation

concerning the Promotion

and Use of Multilingualism

and Universal Access to

Cyberspace

Recognizing that the restriction of the use of multiple languages in the

global information network hinders the securing of universal access to

the digital environment. The purpose is to promote a solution through

international cooperation.

2006

The London Charter for

the Use of 3-Dimensional

Visualisation in

the Research and

Communication of Cultural

Heritage

It covers a wide range of applications such as the arts, humanities, and

cultural heritage that use 3D visualization for research and dissemination

and includes measures to clarify the 3D visualization of digital models.

2015

Recommendation

Concerning the

Preservation of, and Access

to, Documentary Heritage

Including in digital form

In relation to the Memory of the World, UNESCO members should lead

exchanges and cooperation related to preservation and accessibility

enhancement of documentary heritage, emphasizing the establishment

of a continuous network with the private sector and internal and

external expert groups and related institutions, as well as international

organizations.

“

Museum workers” includes all people engaged in the museums recognized by

ICOM and institutions that conduct educational and research activities useful

for museum activities, and they have received training in a field appropriate to

museum activity and operation or have had practical experience equivalent to that.

(ICOM Korea 2013).

In the past, museums and art galleries focused on the role of collection,

research, and exhibition of relics; however, due to recent development and

the diversity of relics, their functions have been expanded to serve as complex

cultural facilities (Choe et al 2019). Choe (2019, 97) emphasized the strengthening

of the educational functions in museums and argued that the roles of curators

should be diversified. It can thus be confirmed that digital education for museum

workers is considered as one of the requirements necessary to enhance the

sustainable development of museums and art galleries.

2. The Necessity of Digital Education

Digital education is crucial for future generations. Attempts to combine

the ICT technology of the fourth Industrial Revolution with existing educational

methods are emphasized. They are based on competency-oriented education

and creative convergence education.

38

Competency-oriented education refers to the cultivation of competencies

necessary for future generations. It cultivates the learners’ ability to utilize

and apply knowledge rather than simply acquiring it (Lim 2019, 260). Major

international organizations such as the OECD and EU have suggested future

core competencies (Jung & Kim 2019, 337). Among them, the Partnership for 21st

Century Skills project recommends the following core competencies.

As shown in Figure 1, the Partnership for 21st Century Skills mentions

competencies such as life and career skills, learning and innovation skills, and

information, media, and technology skills (P21 2009). It emphasizes computational

thinking along with creativity, critical thinking, communication, and collaboration

under information, media, and technology skills that were previously suggested

(

Lim 2019, 259).

In the case of the UK, computational thinking was applied to the regular

curriculum (CAS & Naace 2014, 4). South Korea also emphasizes the significance of

computational thinking in the Software Education Operation Guidelines of 2015

(

Ministry of Education 2015).

Creative convergence education refers to the ability to creatively use and

approach the knowledge and technology of the fourth Industrial Revolution.

Jung and Kim (2019) also suggested an art education plan that strengthens

competencies by converging technological capabilities in artistic creation

and cultural enjoyment. Convergence education started with STEAM (Science,

Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics)

in the United States, which teaches

art with STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics). It helps reinforce

strengths that provide a wide range of convergence education such as creativity

and imagination (Kang 2015, 7).

In the educational field, emphasis is laid on creative convergence education

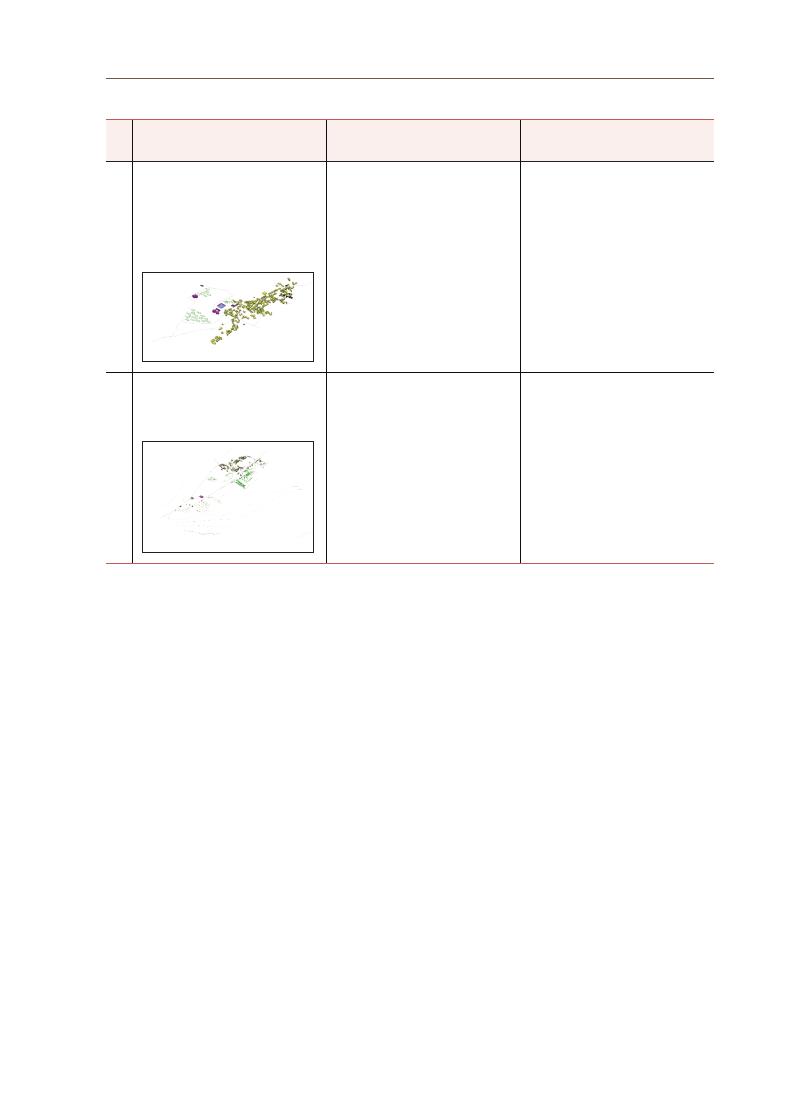

Figure 1. 21st Century student competency framework (partially restructured by the

author) (Source: Partnership for 21st Century Skills 2009, 1)

Life and

Career Skills

Learning and

Innovation Skills

Core Subjects and

21st Century Themes

Information,

Media, and

Technology

Skillds

39

Jong

-w

ook Lee

that encourages creative use by applying competency-oriented computer

thinking and the fourth Industrial Revolution technology to the field of culture

and art. Therefore, this study suggests a digital heritage education program

suitable for the present era by adopting an educational method that applies

digital technology to the field of heritage education. The subject for digital

heritage education is the staff working in institutions related to cultural heritage.

We aim to provide a digital heritage education program that can be applied in the

Asia-Pacific region. Consequently, instances of active studies being conducted

abroad, where digital technology is applied to heritage education, were analyzed.

3. Heritage Education Programs Using Digital Technology

1) CIPA Heritage Documentation Summer School

CIPA Heritage Documentation organized an annual summer school to

educate archaeologists, architects, historians, and surveyors on the correct way

to document, survey, and model cultural heritage. In this program, participants

gained firsthand experience in 3D surveying, photogrammetry, and laser

scanning conducted in the laboratory and on the field.

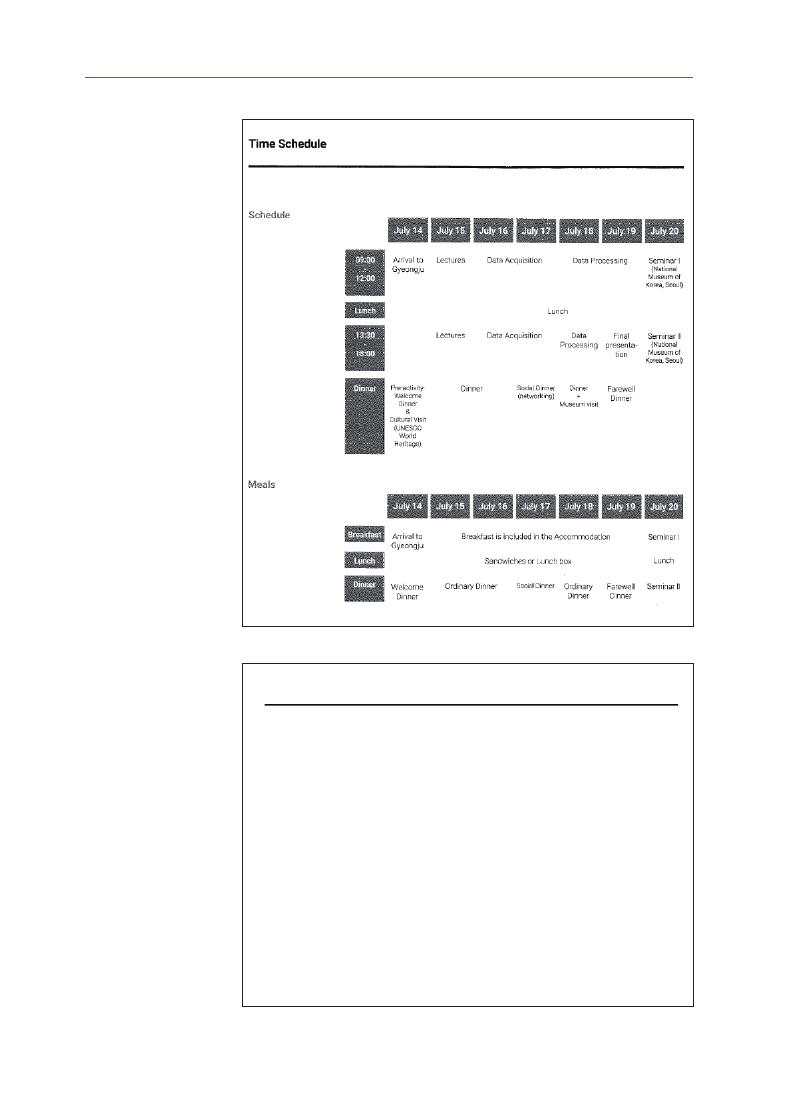

Table 2. The Schedule of CIPA Heritage Documentation Summer School

No.

Date

City

1

July 5–12, 2014

Paestum, Italy

2

July 12–19, 2015

Paestum, Italy

3

August 30 – September 3, 2016

Valencia, Spain

4

July 12–18, 2017

Paphos, Cyprus

5

July 15–21, 2018

Zadar, Croatia

6

September 2019

Manila, Philippines

7

July 14–20, 2019

Gyeongju, Republic of Korea

Figure 2. CIPA SUMMER SCHOOL 2019 in Gyeongju (Source: CIPA Heritage Documentation)

40

Figure 3. CIPA Gyeongju training program schedule (Source: CIPA Lecture Notes)

Figure 4. CIPA Gyeonju lecture content (Source: CIPA Lecture Notes)

Lists of Lectures

01

Andreas GEORGOPOULOS

Photogrammetry

02

Fabio REMONDINO

Laser scanning

03

Efstratios STYLIANIDIS

Topography

04

Abhijit DHANDA

Photography

05

Isabella TOSCHI

Demo CloudCompare

06

Elisa FARELLA

Demo Metashape

41

Jong

-w

ook Lee

Table 3. Cultural Heritage Imaging Programs

Programs

Content

1

4-Day photogrammetry

training

See how to acquire photogrammetric image sets and create scientific 3D

documentation.

Experience how to build 3D content using equipment, image capture setup, and

software.

2

4-Day RTI training

Learn how to use Highlight RTI to create digital representations of various objects.

Develop the ability to implement digital imaging workflows, including capturing,

processing, and viewing RTI digital representations.

3

CHI training with an

expert

4-day training classes on RTI and photogrammetry with direct visits from CHI

experts.

4

Half-day workshop

Learning digital imaging skills in the field of conservation and education. Held for

archaeologists, photographers, or staff of museums or libraries.

2) Cultural Heritage Imaging

Cultural Heritage Imaging (CHI) is a non-profit organization that develops

practical digital imaging and conservation solutions. It leads the adoption of

these technologies by cultural heritage stakeholders to preserve cultural

heritage before it is lost. Its goal is to universalize technology so that people

worldwide can document their cultural heritage and preserve and protect it

for future generations. CHI technologies comprise new and easily learnable

imaging techniques (photogrammetry and reflectance transformation imaging (RTI)) along

with various tools, skills, and training.

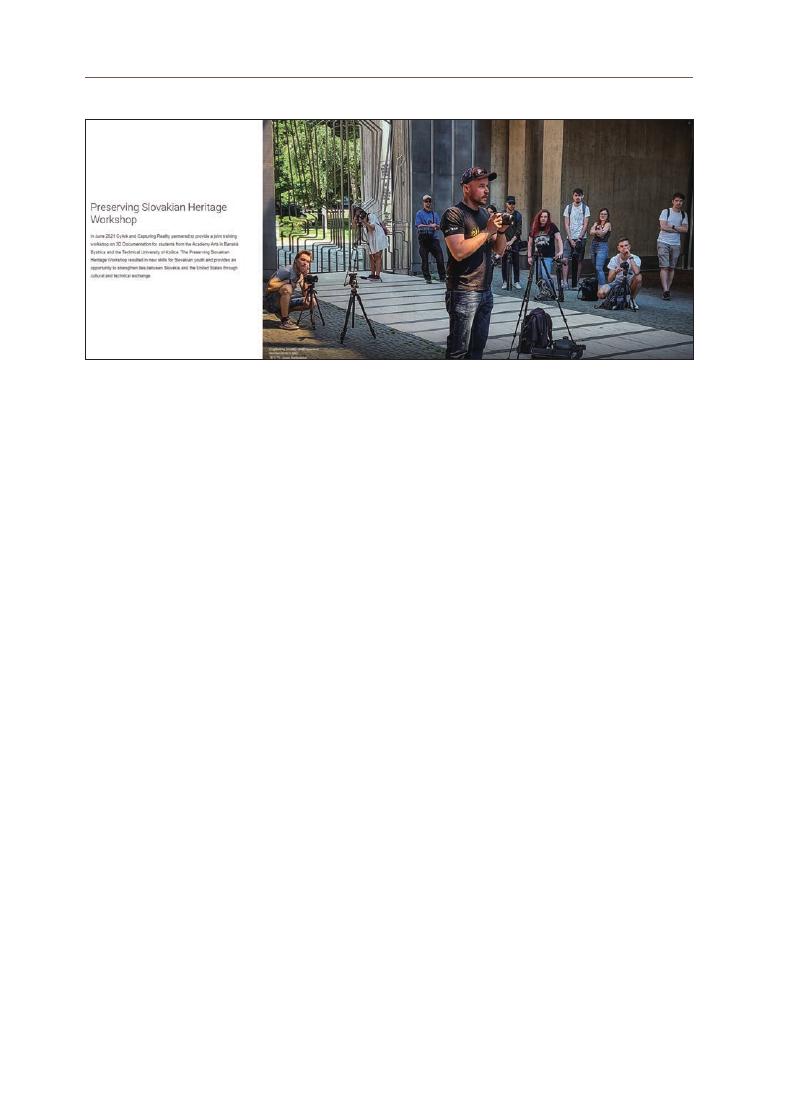

3) CyArk

CyArk is a non-profit organization established in 2003 with the goal of

archiving, storing, and sharing digital heritage. Currently, over 200 sites have

been documented, and 3D documentation training programs are provided

for students through workshops. In June 2021, CyArk and Capturing Reality

collaborated to provide a joint educational workshop on the topic of 3D

Figure 5. Educational environment at Cultural Heritage Imaging (Source: CHI)

42

documentation for students at the Academy of Arts in Banská Bystrica and the

Technical University of Košice. The two-week course provided students with

training to record historical sites using photogrammetry techniques and to

create virtual reality scenes and 3D models

1. Digital Records in the Field of Heritage

The International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) adopted the

‘

Principles for the Recording of Monuments, Groups of Building and Sites

(

1996)’

in 1996, stating that records are an important part of the preservation

process (ICOMOS 1996, 49). Recording has become an indispensable process in the

conservation of cultural heritage, and digital technology has helped to improve

the speed, accuracy, and data quality of cultural heritage documentation. Digital

technology enables the recording and analysis of high-quality cultural heritage

data at a high speed, and the results of the analysis facilitate the establishment

and implementation of cultural heritage conservation plans. These results

were shared by experts and related parties and used in the conservation,

management, and utilization of cultural heritage.

2. Digital Recording Technology

Several technologies can be used to record cultural heritage, and the

application of these technologies depends on the type and properties of the

cultural heritage being documented. The format of digital recording includes 2D

images, 3D shapes, sounds, and motions. Figure 7 shows how 3D data of cultural

heritage is acquired through contact and non-contact methods depending on

Figure 6. Preserving Slovakian Heritage Workshop at CyArk (Source: Cyark nd)

Ⅲ. Digital

Recording

Technology

43

Jong

-w

ook Lee

Figure 7. Classification of 3D scanners by scanning method (edited by the author) (Source: Cultural Heritage Administration

2018, 12)

whether the scanner is in contact with the surface of a relic or not. The non-

contact method is further bifurcated into an active method, which is a distance-

based method obtained by firing a laser or light, and a passive method, which is

an image-based method that calculates 3D data by recognizing an object using

an image sensor. The use of the non-contact method for data acquisition is

suitable for cultural heritage sites to maintain their integrity.

Figure 8. Investigation technology according to the characteristics and size of the object

(

Source: Historic England 2018, 2)

44

1) 3D scanning

3D scanners record the 3D coordinates of numerous points on the surface

of an object within a relatively short time period. In this process, a laser beam

is projected onto the surface of the object (Boehelr et al 2001, 1). The 3D scanner

operates through the time-of-flight method, the phase shift method, and the

triangulation method. The precision scanner uses the triangulation method

(

Cultural Heritage Administration 2018, 13).

2) Photogrammetry

Photogrammetry is a technology that extracts 3D form information by

acquiring images of stationary objects from various angles and positions. This

is an image-based modeling technique included in SfM (Structure from Motion)

technology that interprets the structure of an object from motion.

In this study, educational content on 3D data generation of cultural heritage

was developed, focusing on photogrammetry technology, so that workers in

the field of cultural heritage can acquire data in a short time at a relatively low

price and with easy access. The technical characteristics of 3D scanning and

photogrammetry are compared in Table 4.

Table 4. Comparison of technical characteristics of 3D scanning and photogrammetry

Categories

3D Laser Scanning

Photogrammetry

Technology base

Distance

Image

Price

Expensive

Cheap

Operability

Low

High

Date Acquisition Time

Long

Short

Modeling of Complex

Shape

Difficult

Easy

3D information

Direct Acquisition

Extraction

Distance Dependence

High

Low

Space Dependence

High

Low

Material Dependence

High

Low

Light Dependence

Varies by Machines

High

Date Size

Large

Depends on Resolution

Texture

Low resolution

Including

Open Software

Few

Several

45

Jong

-w

ook Lee

IV.

Photogrammetry

1. Basic Principles

1) What is photogrammetry?

Photogrammetry is a method of measuring an object by taking its image.

Qualitative data, such as the color of the object and the degree of wear, and

quantitative data, such as the height and size of the building, can be obtained

from the survey by measuring the acquired photos.

Photographers must follow certain rules and procedures to obtain correct

data through photogrammetry. Photogrammetry proceeds in the following

order: 1) image capture, 2) image matching, and 3) point cloud generation. The

preparations differ depending on the size, characteristics, and condition of the

object. This photogrammetry course focused on the method of photographing

artifacts of 20cm×20cm or less so that relatively small artifacts can be

photographed.

2) Needs

Photogrammetry supplies for small artifacts include a DSLR camera, tripod,

lighting, white background paper, release, color reference card, turntable, and

software (3DF Zephyr, Reality Capture, etc.).

2. Photography

Photography refers to recording the shape of an object by adjusting the light

sensitivity, aperture, and exposure time. To use photogrammetry technology

correctly, an understanding of photography and the art of handling cameras is

essential. It is necessary to check the basic parameters of sensor sensitivity (ISO),

aperture, and shutter speed among the main operating elements of the camera

to properly record the shape of the artifact.

Figure 9. The three factors of photography (Source: Hamberger Fotospots, n.d.)

46

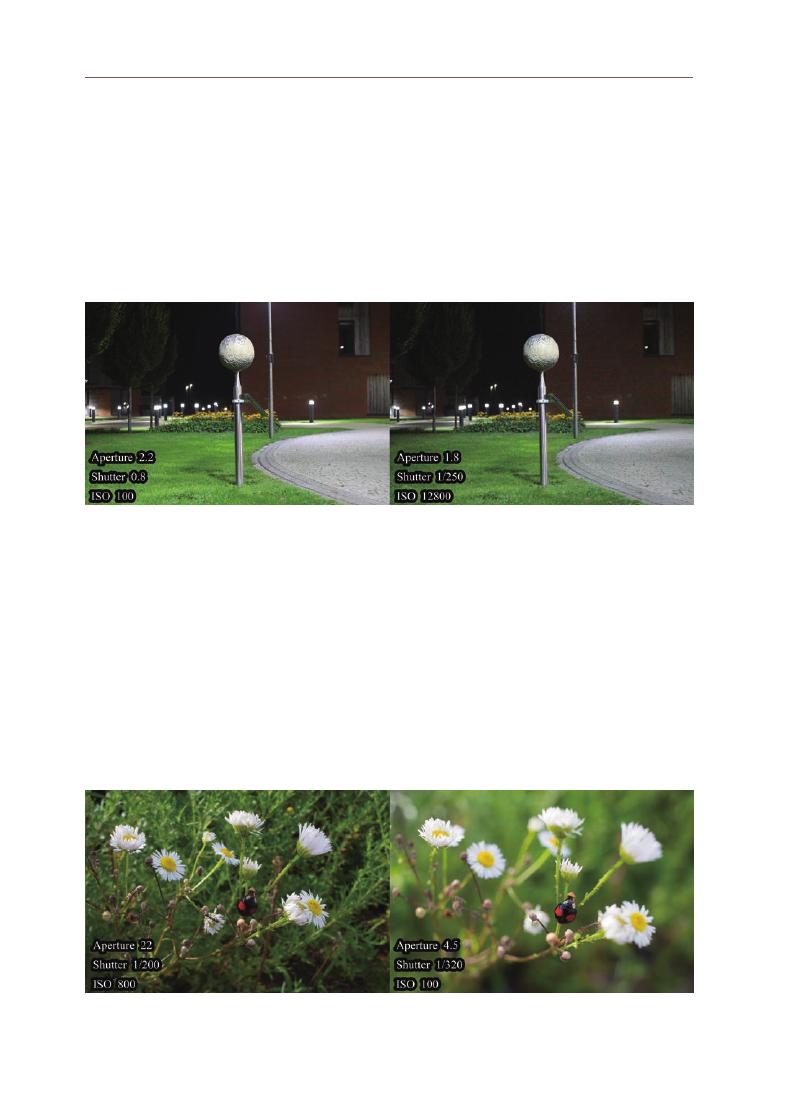

1) Sensor sensitivity (ISO)

ISO is a measure of the sensitivity of a camera’s image sensor. Until

the 1980s, each country had a non-uniform standard for sensitivity, but the

International Organization for Standardization set a film sensitivity standard that

can be used worldwide. The sensitivity of the sensor is often called ISO sensitivity.

In general, the lower the sensitivity of the camera, the less light it receives, and

the higher the detail and saturation of the picture, the clearer is the picture.

2) Aperture

Aperture is defined as the degree to which the lens opens. The light hits the

sensor through the lens, and the amount of light is limited by the degree to which

the lens is opened. When the aperture is opened, the amount of light increases,

and the image becomes brighter. Consequently, the depth of focus becomes

shallow and the front and rear parts except for the focused part blur the image.

Conversely, if the aperture is closed owing to the high number of apertures, the

amount of light is reduced. Consequently, the depth of focus is deep and clear

images can be obtained.

Figure 10. Comparison of quality degradation according to ISO manipulation (ISO 100 versus ISO 12800) (Source: Kim 2019)

Figure 11. Comparison of changes in the focus of photos according to the manipulation of the aperture value (aperture 22

versus aperture 4.5) (Source: Kim 2019)

47

Jong

-w

ook Lee

Figure 12. Comparison of photos according to shutter speed manipulation (shutter speed 1/3200 sec. versus 1/15 sec.)

(

Source: Kim 2019)

3) Shutter Speed

The shutter speed or exposure time refers to the amount of time the image

sensor inside the camera is exposed to light. The faster the shutter speed, the

clearer the dynamic picture can be obtained, but the lesser the light entering

the sensor, the darker the picture can be obtained. Furthermore, the slower

the shutter speed, the harder it is to capture dynamic photos, but the longer the

sensor is exposed to the light, the brighter the photos can be obtained at times in

places with low light, such as at night or indoors.

3. Application to Small Objects

Photogrammetry requires the application of different surveying techniques

depending on the size, shape, and condition of the object. It is necessary to pay

attention to the focal length of the lens, the control of the light, and the location

of the artifacts while conducting it. In the case of small artifacts displayed in

museums and art galleries, it may be advantageous to use a macro lens that can

take pictures at a short distance from the subject. It is recommended to set up

the lighting and tents in a manner that can disperse the light evenly and control

it. Additionally, high-quality data can be obtained by improving the shooting

environment using turntables, scale bars, and color reference cards.

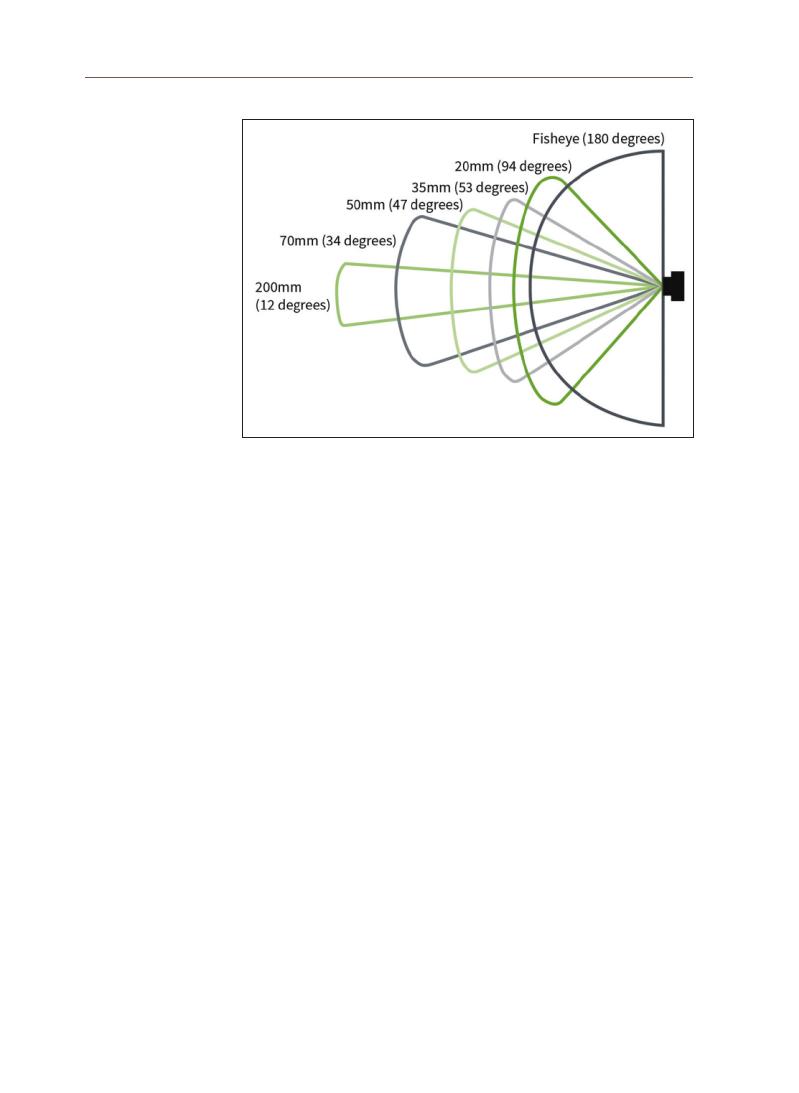

1) Macro lenses

A macro lens is a lens that is optically designed to focus closer to a subject.

Regardless of the focal length of the lens, it can be used if it has a macro

function; however, as it gets closer to the subject, it is easier to use a wide-angle

lens to capture the entire range of the artifact. However, sometimes a telephoto

lens is needed to photograph artifacts such as coins. A 40–60 mm lens is called

a standard lens, a lens with a shorter focal length than that of the standard lens

48

is called a wide-angle lens, and a lens longer than the standard lens is called a

telephoto lens.

2) Lighting tent

In the case of small artifacts, shadows may occur depending on the location

of the lighting in the studio, which may prove to be problematic in acquiring data.

Accordingly, shadows on the relic should be minimized, and the material of the

relic that does not reflect light is ideal to obtain photos for photogrammetry.

Moreover, the light should be evenly dispersed. There is a technique to use the

tent to disperse the light. After installing the tent, if LED lights are installed

outside it, the light is evenly dispersed inside the tent. The tent is easy to set up

so that the light can be dispersed evenly.

3) Turntables

Turntables are used while photographing small artifacts. The turntable is

used to rotate the artifact while the camera is fixed at a particular spot. The

advantage is that 360-degree recording is possible with the camera, lighting,

and tent fixed, so the intensity of light can be uniformed. Additionally, it reduces

the acquisition time of image data by reducing the time required to set up the

camera and lighting.

Figure 13. Shooting range according to the focal length of the lens

(

Source: Historic England 2017, 29)

49

Jong

-w

ook Lee

4) Scale bars

The scale bar acts as a measure to check the distortion that occurs during

the shooting. When shooting an artifact, the actual size of the artifact can be

checked, which is necessary to create an accurate 3D model of the artifact.

5) Color reference card

The color checker helps photographers adjust the white balance by checking

the color of the image on the computer. White balance refers to adjusting the

color balance of the color to match it to the original one by neutralizing the color

of the photographed light.

Figure 14. Dispersion of light and shadow

removal using a tent (Source:

Historic England 2017, 107)

Figure 15. Tools used to photograph small artifacts (Turntable, scale bar,

and color checker) (Source: Historic England 2017, 76)

Figure 16. The scale bars produced by Cultural Heritage Imaging (Source: Cultural Heritage Imaging, n.d.)

50

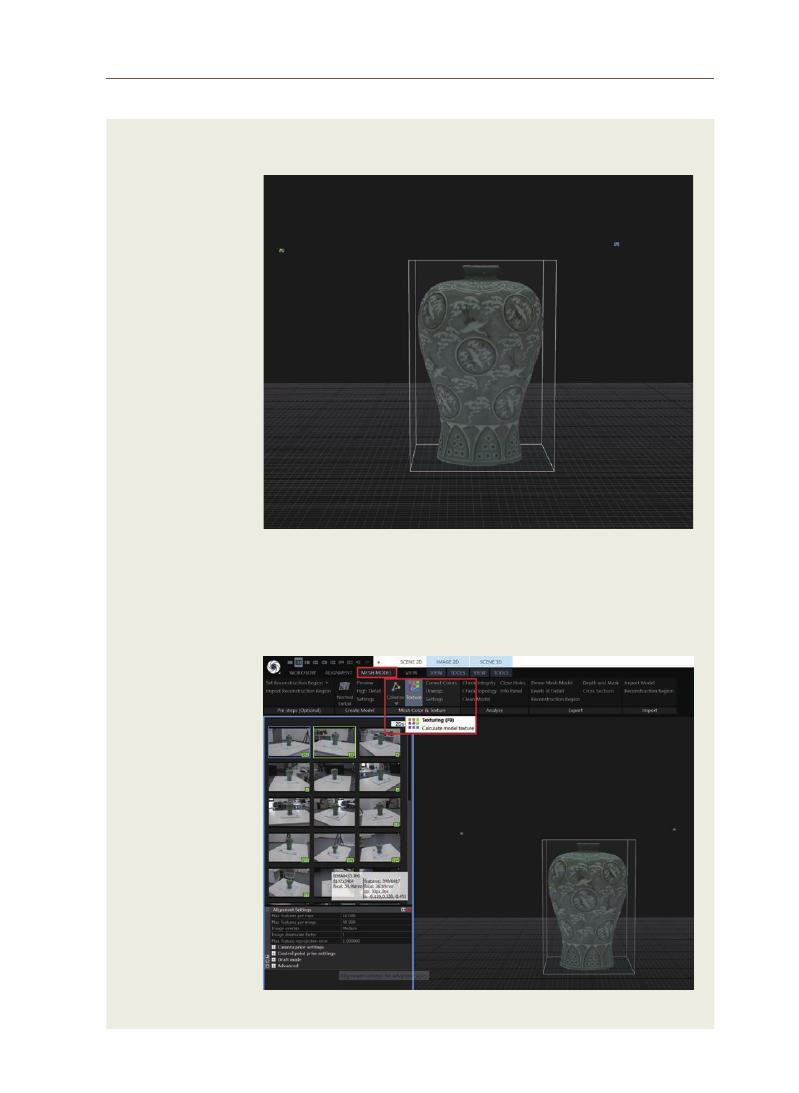

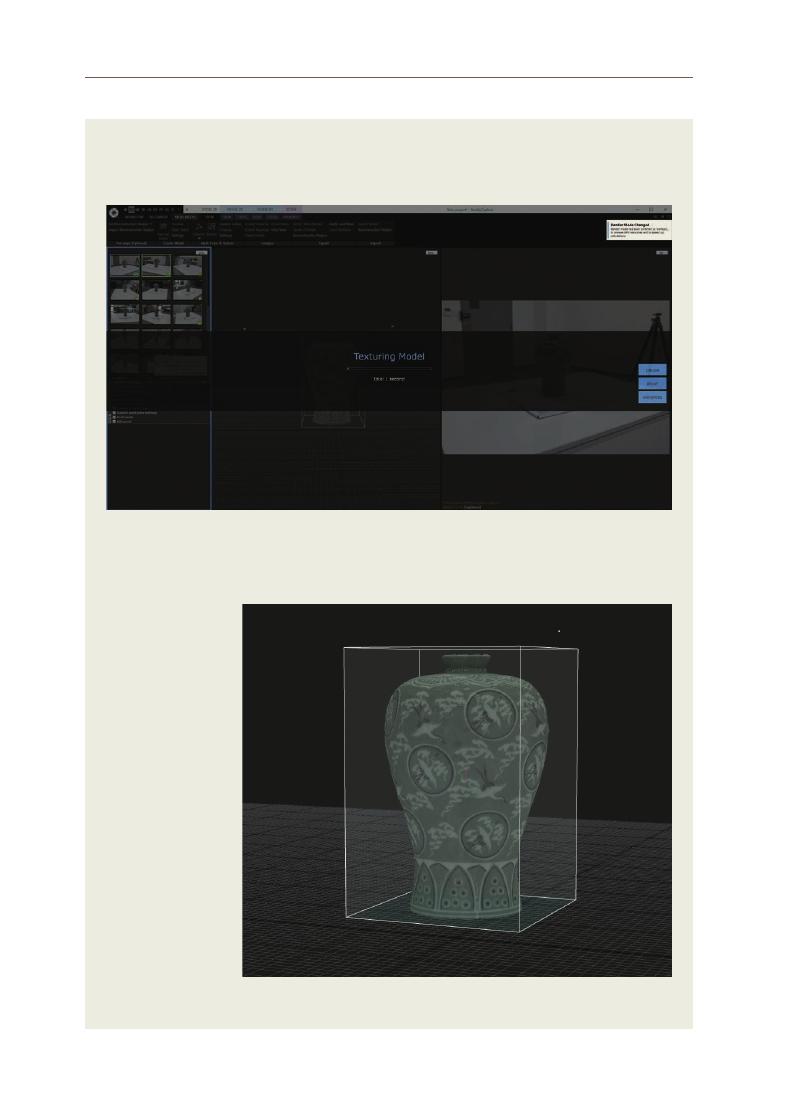

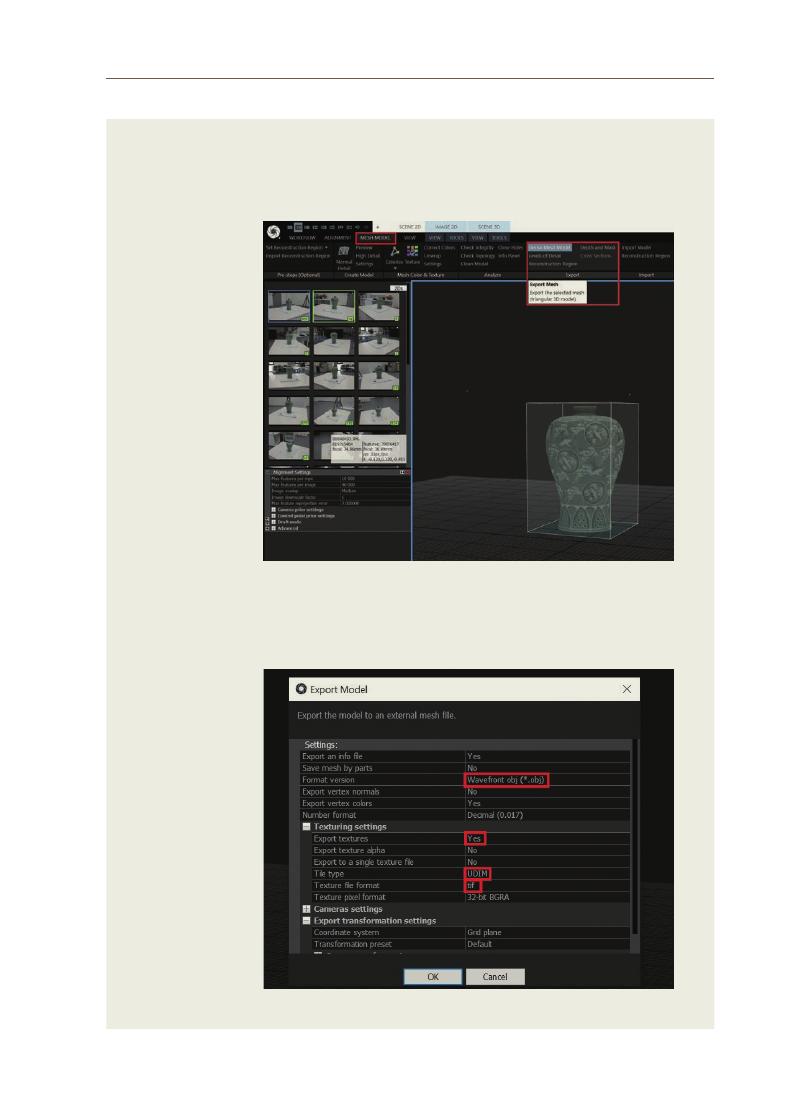

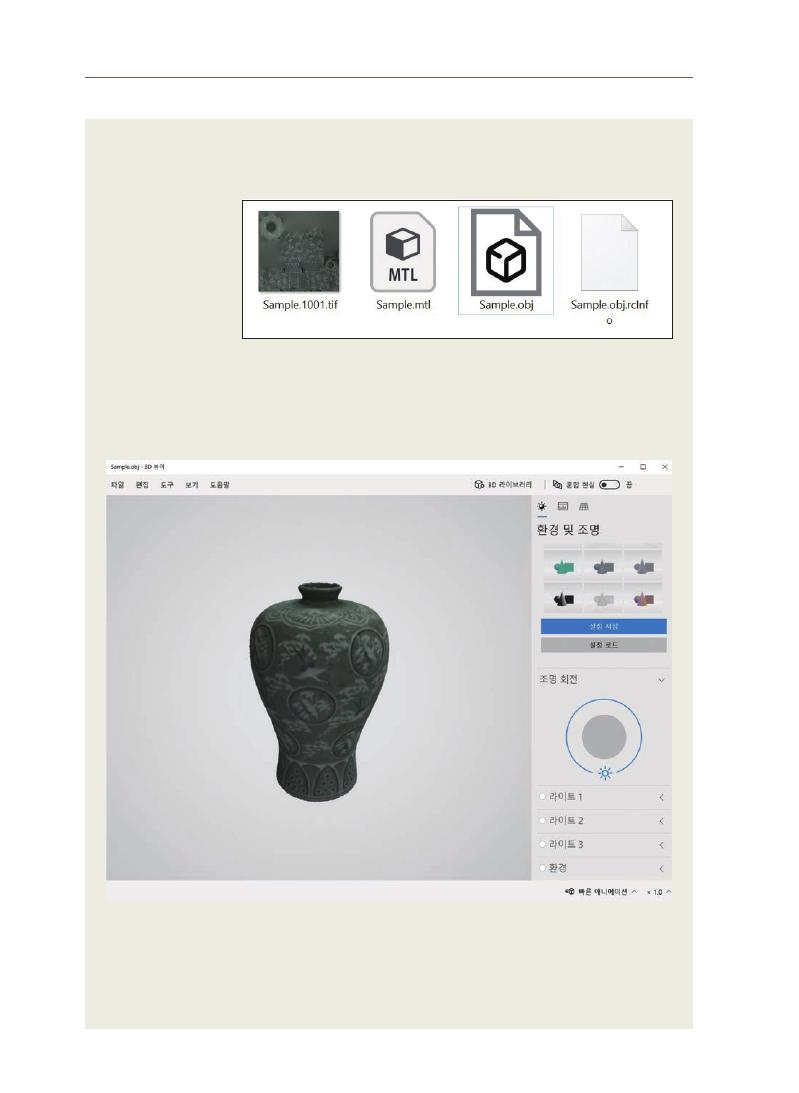

4. Practice

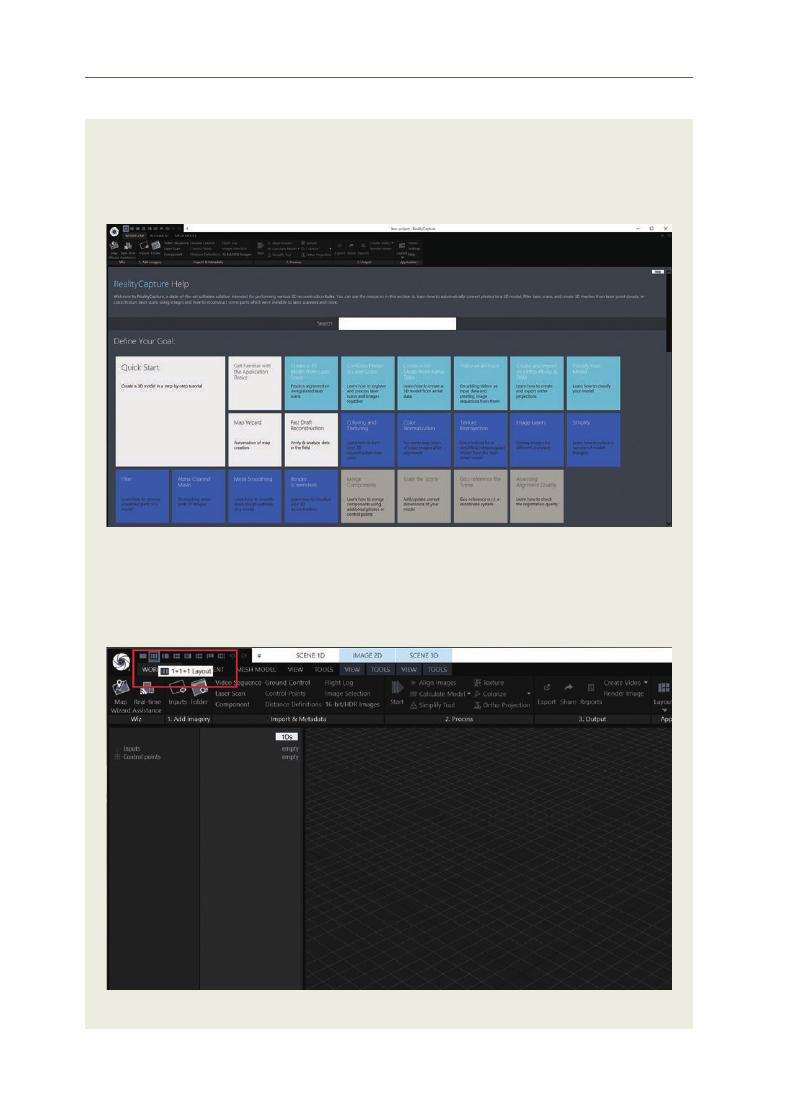

In this photogrammetry handbook, Reality Capture and 3DF Zephyr were

the programs used for aligning the photos of a relic. Reality Capture especially

provides the advantages of good performance, fast processing speed, and easy

operation. This handbook dealt with a replica of Goryeo celadon, one of Korea’s

representative artifacts, applied with the inlay technique as a target artifact. The

procedure for generating a 3D model of the artifact utilizing photogrammetry is

as follows (see Appendix 1).

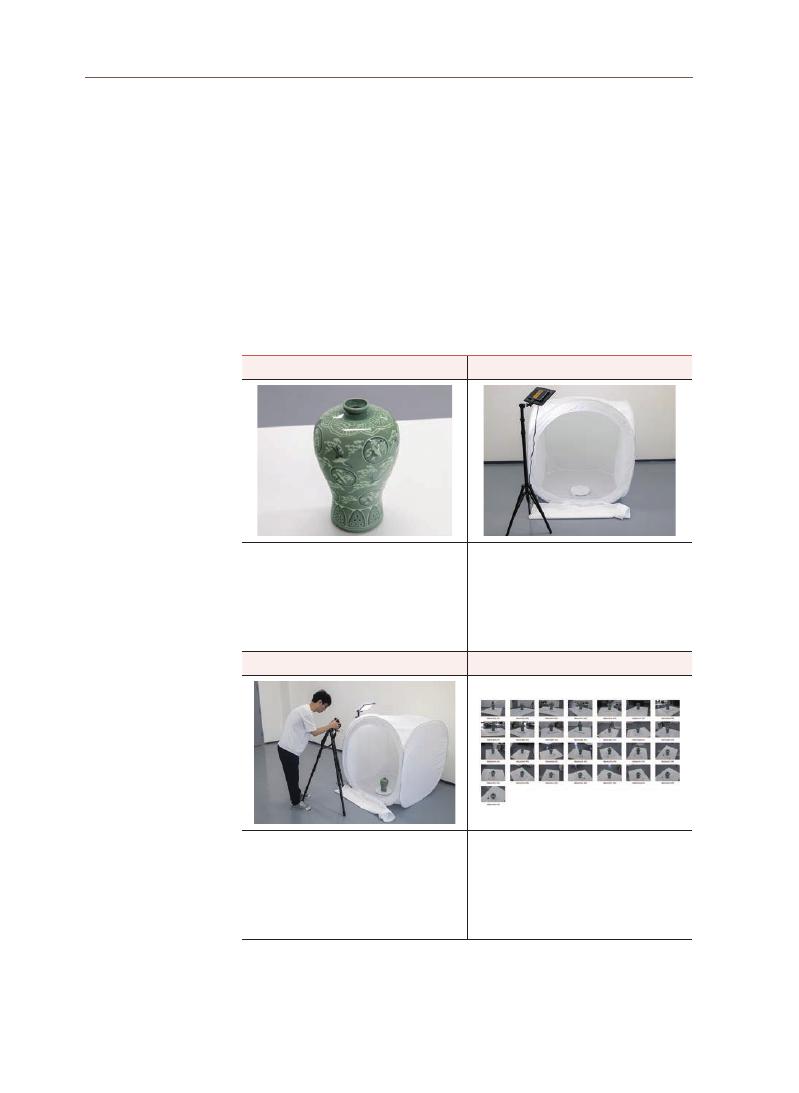

Table 5. Practice creating 3D models of small artifacts using photogrammetry

1. Selection of an artifact

2. Setting up the environment

Select the artifact you want to create

a 3D model of from the museum

or art gallery. Since the difficulty of

acquiring image data varies depending

on the size and shape of the artifact, a

simple artifact is recommended in the

beginning.

Set up the environment by installing

tents, lighting, turntables, color

checkers, and scale bars. Rather than

direct light, it is better to have an

environment where the lighting light

passes through the tent and the light is

dispersed evenly.

3. Taking an Artifact

4. Data Acquisition

Rotate the turntable and take pictures

of artifacts. It is recommended to rotate

the turntable at an angle of about 15

degrees. When shooting, consider the

focus and image shake.

Acquire image data using photography

skills suitable for the artifact. When

acquiring image data, the more the

overlapping parts of the image, the

better the image alignment. The height

of the camera is adjusted based on the

artifact, and several shots are taken.

51

Jong

-w

ook Lee

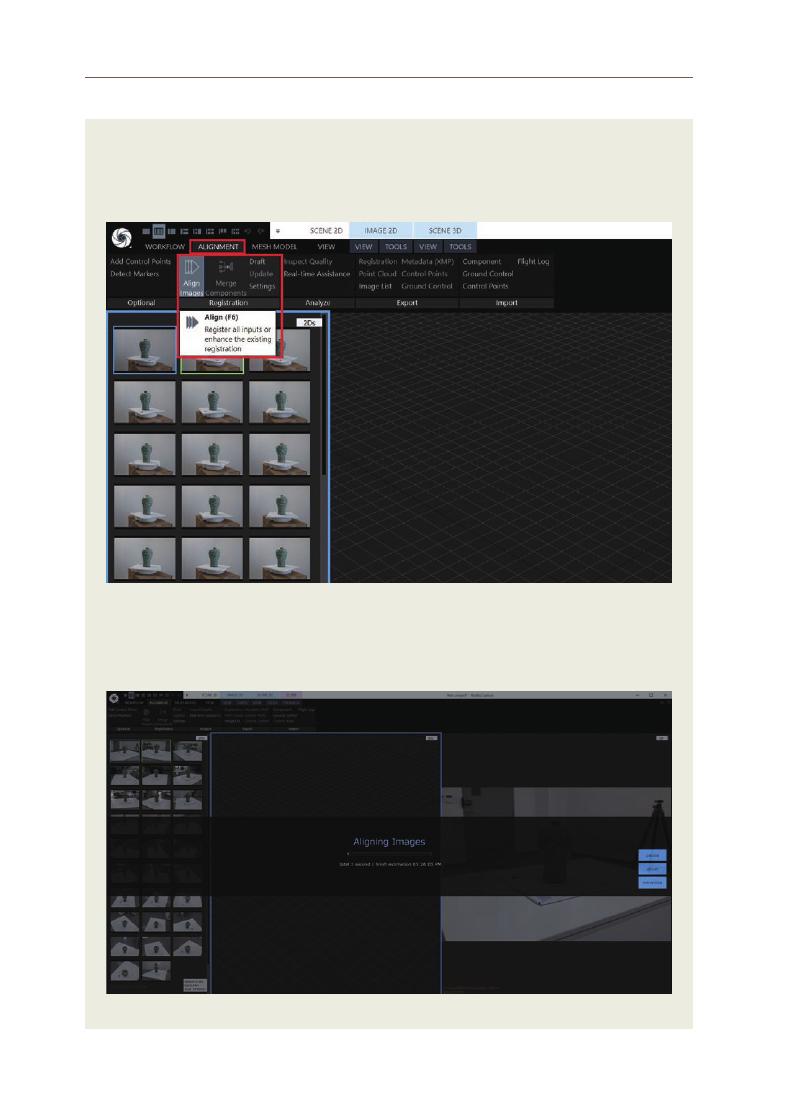

5. Data Alignment

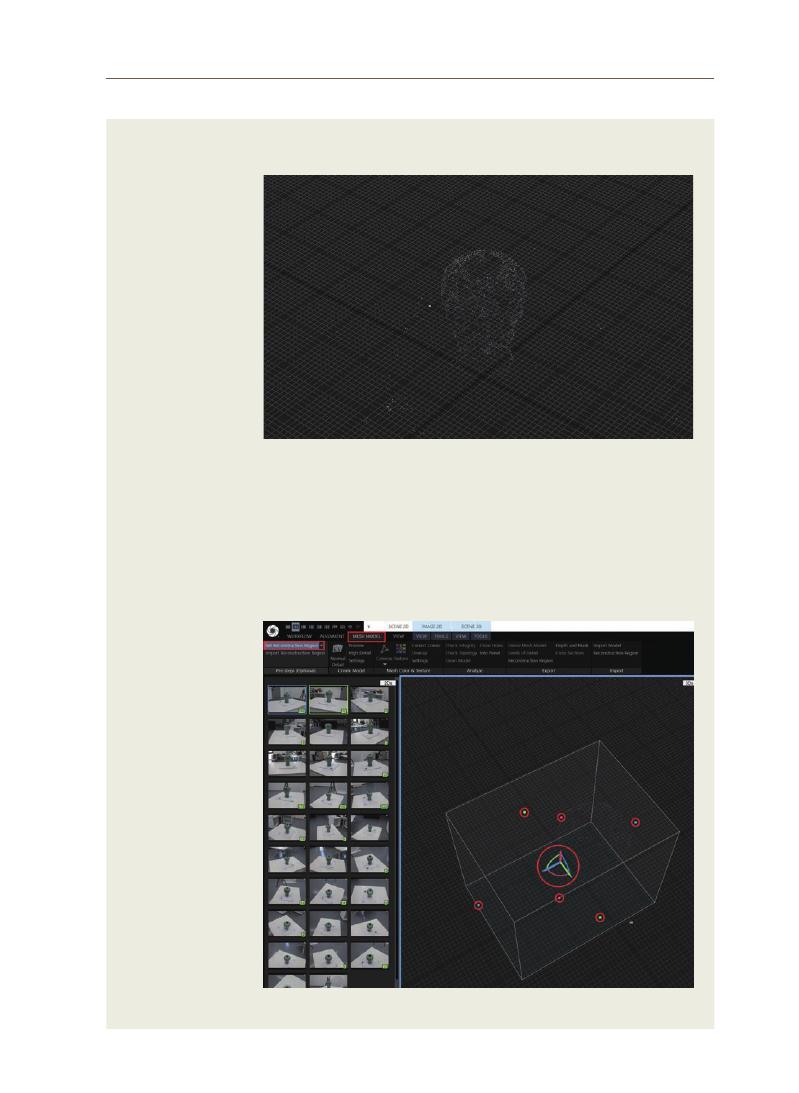

6. Generating High-Density Point

Clouds

Use the application to match the artifact

data. The initial data arrangement

produces a low-density point cloud.

Based on the generated low-density

point cloud data, more points are

connected to create a high-density point

cloud.

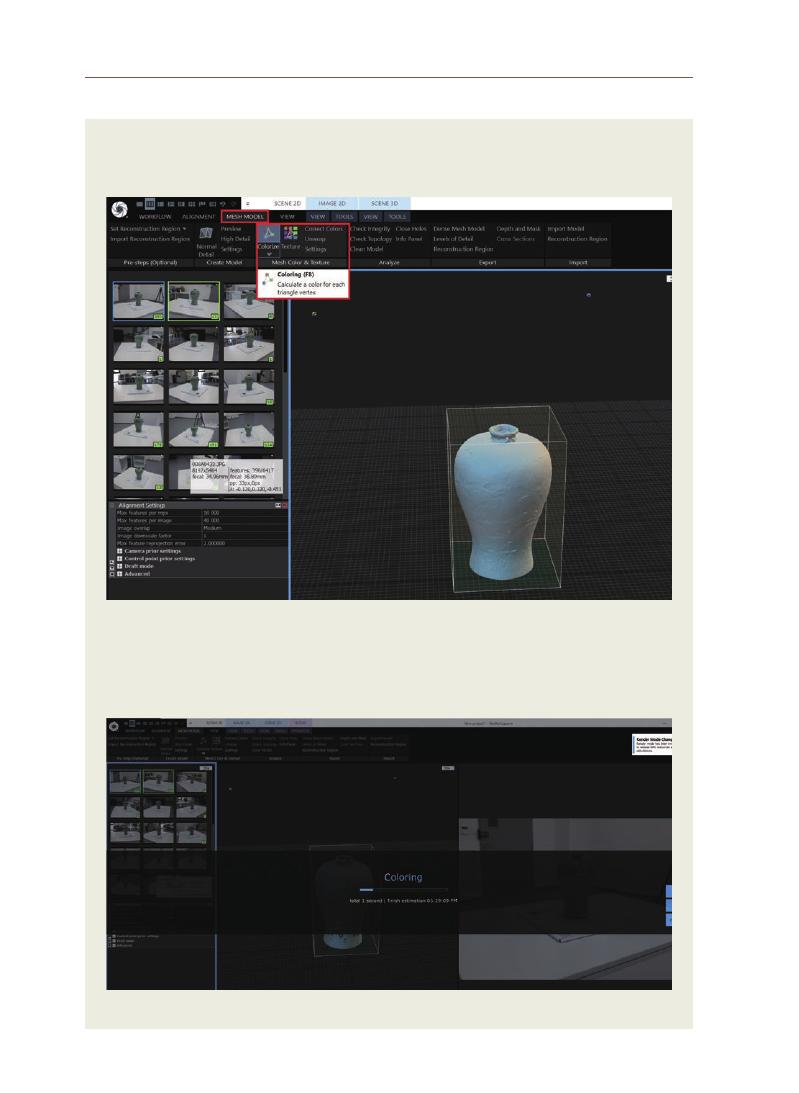

7. Generating Mesh Data

8. Generating Textured Mesh

and Export Object File

Generate mesh data based on high-

density point clouds.

If the generated data is processed into a

textured mesh and exported as an object

file (OBJ), the 3D model can be used in

applications that support OBJ extension.

This study aimed to produce a photogrammetry education program for 3D

digital scanning of cultural heritage for professionals working in the field of

heritage. The concepts and definition of digital heritage were researched and

charters related to it were examined. Digital heritage has been defined in various

forms and can be summarized as computerized materials with lasting value that

should be preserved and transmitted to future generations (Lee 2019). After the

UNESCO Charter on the Preservation of Digital Heritage was published in 2003,

the concept of digital heritage was expanded and discussions on digital heritage

were actively conducted.

Chapter 2 examined the definitions of the types of professionals in the

V. Conclusion

52

heritage field and the museum workers discussed in ICOM to examine the

importance of digital heritage education. The museum has particularly

developed into a complex cultural facility due to the diversity of the artifacts on

display. With the advent of the information age, museum curators must acquire

knowledge about digital heritage. Additionally, as the ICT technology of the fourth

Industrial Revolution is being applied to educational methods, the necessity of

digital education for workers in the heritage field has been in demand. Currently,

more cultural heritage education programs using digital technology are being

actively conducted in European countries than in the Asia Pacific region.

Digital recording technology plays an important role in the conservation of

cultural heritage, and the ‘Principles for The Recording of Monuments, Groups

of Building and Sites (1996)’ codified the importance of documenting cultural

heritage. In this study, 3D scanning, and photogrammetry were compared, and

the photogrammetry technology, which provides the advantages of relatively low

price, easy access, and fast data acquisition, was selected as the target of the

education program.

Photogrammetry is based on photography, and the adjustments in ISO

(

Sensor sensitivity),

aperture, and shutter speed play significant roles. The

handbook selected relatively small relics, found in huge proportion in museums,

and accordingly, a macro lens, a tent for lighting control, a turntable, a scale

bar, and a color checker were selected. The practice module was developed

by confirming the need for the photogrammetry technology studied in this

paper, and the procedure of 3D model production was explained with actual

photographs. Celadon, one of the relics mainly found in the Asia-Pacific region,

was selected as the target relic. A celadon is apt to teach the concept of light

control and is advantageous because beginners can easily access them due

to their simpler appearance. Then, using Reality Capture, which is easier

to operate than other softwares, the practical methods and procedures for

photogrammetry were introduced.

Although this study did not provide an in-depth understanding of

photogrammetry, it served its purpose of providing a working knowledge of

its techniques to the laypeople working in the field of heritage. It allowed for

non-major professionals in the heritage field to apply digital technology to

the cultural heritage easily. It made it easy for them to acquire the theoretical

understanding and practical skills regarding digital heritage, digital recording